Engaging with South Africa, Part Two: David Goldblatt

Last week, Arthub launched a series of in-depth interviews with South Africa based artists as a post Cape Town Art Fair analysis. The exchanges were instigated by Arthub’s Director and Founder, Davide Quadrio, following his moderation of the panel discussion Cross Cultural Encounters, Post Colonialism and Appropriation in the Age of Artistic Mobility, at the fair this past February.

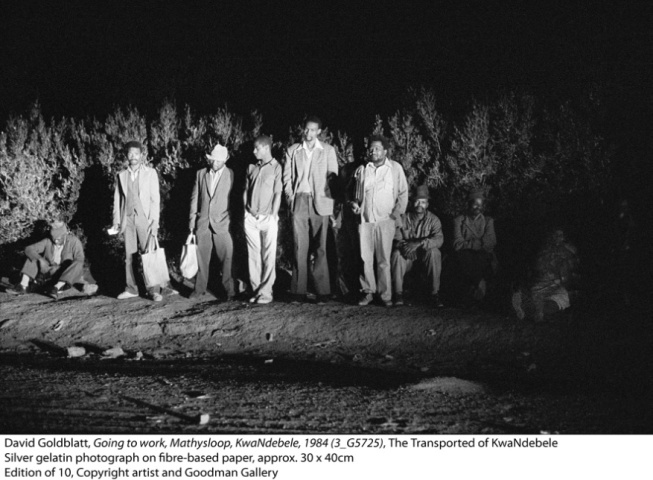

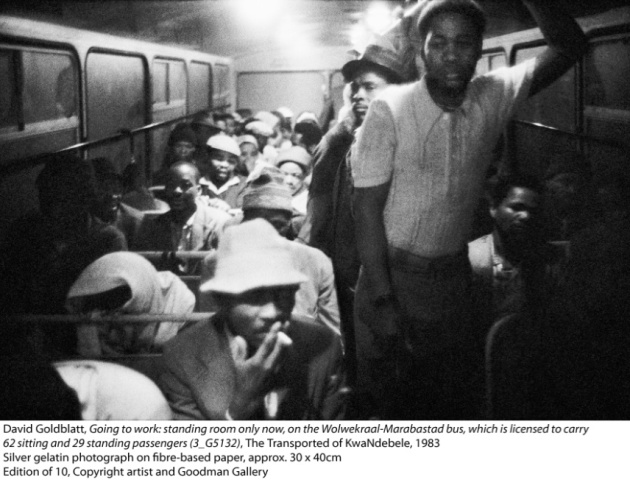

Arthub’s Head of Production and Assistant Curator Ryan Nuckolls had a chance to speak with South African photographer David Goldblatt about the many ways in which apartheid has impacted his work. David (b. 1930) has been taking photographs since the 1950s. At that time, he was shooting the unfolding political campaigns mounted by the Congress Alliance, but it wasn’t until 1964 that David received his first career break, when Sally Angwin, the editor of the avant-garde magazine South African Tatler, started passing assignments his way.

As a self-appointed forensic witness, apartheid was often the central subject in David’s work, but his true fixation was with photographing and understanding the values of South Africa and the individuals within it. Read on to learn more about photographer David Goldblatt’s artistic motivations for past projects (dating back to the beginning of his career), as well as his plans for future series.

The text below is an abridged version of Arthub’s interview with David Goldblatt. Read the full copy here.

Ryan Nuckolls (RN): It seems that labels are very powerful in South Africa. For example, you are a White English-speaking Jewish South African. These are labels by which many would define you. You have referred to yourself as un-appointed unlicensed critical observer. I would like to ask you about one more label—how do you feel about the term artist?

David Goldblatt (DG): I must say, I find the word artist to be a rather presumptuous kind of title. To me, art is a grey area. I understand we need shorthand ways of comprehending certain subjects, so sometimes it’s a good idea to use a term like the arts or artists—regardless of whether I’m comfortable with it. Here, I will follow the Oxford dictionary, which defines art as either a craft or an attempt at a transcendental statement. I wouldn’t presume to make such a statement, but I do believe that I am a good craftsman, or at least I hope so anyway.

Whether or not my work can be regarded as art is not terribly important to me. If people choose to regard me as an artist, then it’s up to them. Admittedly, I make my living nowadays by the sale of prints. This is to me, a very interesting, but strange place to be in, because I think the international art market is a bit of a bubble. The world has taken to photography in quite a big way and regards it as art (whatever that may be). I am a part of that – I don’t feel altogether comfortable with it – but I am very happy that I’m being paid ridiculous amounts of money for prints. I would never buy my prints for those prices.

At the moment, we are in throes of a situation in South Africa—recently, students have being trashing art, they’ve burnt paintings and photographs. This is a disturbing matter; I believe these students are just one step away from matches. First, they burn art and then they burn people. In 1986, at a large outdoor rally in Soweto, Winnie Mandela is recorded declaring, “We have our matchboxes. We have our bottles… with necklaces, we will liberate the country”. Here she was referring to the nation’s ability to violently protest and attack their opposition (necklacing is the execution and torture of individuals by forcing motor car tires, filled with petrol, around their chest and arms, and setting it alight).

The actions of these artists – if I can use that term now – is a very serious matter (not just idle talk). I think the artists of this country have been remiss in not standing up and talking or rather shouting about what has happened to them and to their fellow countrymen. I understand the need for direct action in order to bring about change, but South Africa has a democracy—as was proven yesterday by a very significant judgment in our constitutional court.

I believe the essence of democracy is discussion. When we have differences within a democratic society, we are able to settle our differences by talking. Parliaments, media platforms, freedom of expression, these are all important aspects of a democratic state. When I’m threatened, which is how I feel after the burning of somebody else’s work, I take that as an infringement on my right to express myself. When you’re attempting to achieve your ends by throwing human shit or using matches – acts that inevitably lead to fists and guns – these are methods of direct action that seriously infringe upon democracy.

RN: Following the 1948 National Party election you considered leaving South Africa, fearful of raising your kids in a highly racist society. I understand that in the following years you realized that leaving would have meant becoming an alien forever; whether you decided to immigrate to Israel or Europe you would never have been as familiar with the people and the land in the same way you are connected with South Africa. In past moments of self-censorship and fear, have you ever regretted your decision not to leave?

DG: I’m delighted that I stayed in South Africa and I would hate to be forced to leave now. I think the only circumstance in which I would contemplate leaving, even at this ripe age, is if we were seriously overcome by intolerable violence. And we certainly haven’t reached that stage yet.

The violence being exercised now is a threat to our freedom of expression, but hasn’t yet become a threat to our existence. However, it has to be said again, we are currently in a situation in which people who are regarded as foreign, particularly in the townships, are being targeted. Their businesses have been raided, looted and destroyed. This is the antithesis of freedom, free market values and democracy. South Africa is governed by the rule of law, which simply means that there are guidelines by which the society has agreed to govern itself. And when you seriously impede on those laws and threaten the validity of the state’s infrastructure, then you’re in a very vulnerable place.

RN: I know you do not consider yourself a political activist, but throughout your career you have been involved in politics, either as a critic of exploitative labor practices or by capturing the structural inequalities that exist in both literal and metaphorical manifestations. Do you think your work has helped shape the way non-South Africans understand and relate to what happened during Apartheid?

DG: I find it very difficult to make any kind of assessment about the impact of my work on the world. Who knows whether it has had any influence on the actions of others—what they may or may not have done otherwise. It’s a topic that I’ve never really explored. Every now and again, I’m warmed by people saying how much they respect the work I’ve done. I’m very glad for these sentiments, honored really, but honestly, I don’t think that my work is the kind that influences people. That doesn’t mean that I don’t pursue these loftier goals and that I don’t believe that the work I started fifty years ago isn’t necessary. I have to do what I do. It’s my way of standing up and being counted, and I hope I go on doing it until the day I die.

RN: At the beginning of your career, you said that part of your motivation for becoming a magazine photographer was driven by an ambition to tell the world what was happening in South Africa, by using this miraculous instrument that allowed you to touch the real world, while simultaneously abstracting it. Publications like Life and Picture Post allowed you to step through a window into a different world and you wanted to help others do the same. Eventually, you realized, maybe the rest of the world wasn’t very interested in what was happening in South Africa—do you still feel this way? Do you have a desire to share the country that you know so well with the rest of the world or do you think in some ways it’s a culture that as a non-native is almost incomprehensible from the outside?

DG: It sounds really selfish, well it is really selfish, but ultimately I’m engaged in a conversation with myself – it’s nothing more than that. When I say myself, I like to think that this includes my South African compatriots. A long time ago, in 1968, I stopped trying to talk with people outside of South Africa about my work, because I realized that it was very difficult to convey the essence of the photographs that I’m interested in making. I had to explain to them what the work was about; it was like explaining a joke. When you explain a joke its no longer funny. Whereas, when I’m talking (or think that I’m talking to South Africans) I’m often aware that somebody, even someone whom I’ve never met, in some other part of the country, could be saying, “that photograph really spoke to me, I like what he’s saying”. Even if they are responding: “I don’t like what he’s saying”, at least I know the work will resonate with them on a cultural level.

At the end of the day, the fact that I participate in international exhibitions and continue to publish books means that I do want my work to be seen. I hope that it does reach people, but I don’t assume that it does. And I certainly don’t assume that it has any more importance to people, than the rest of the general mess of information out there does.

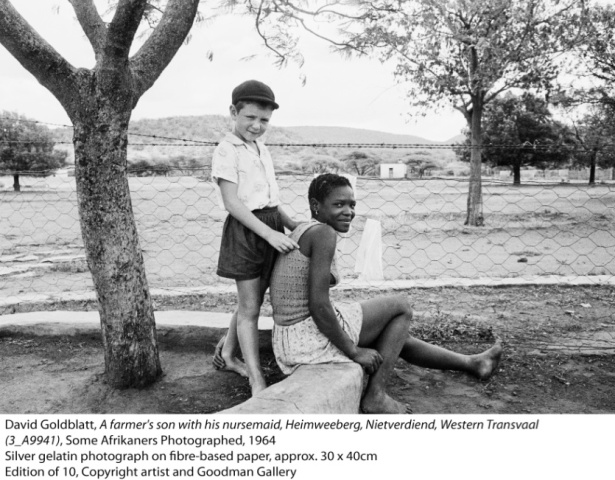

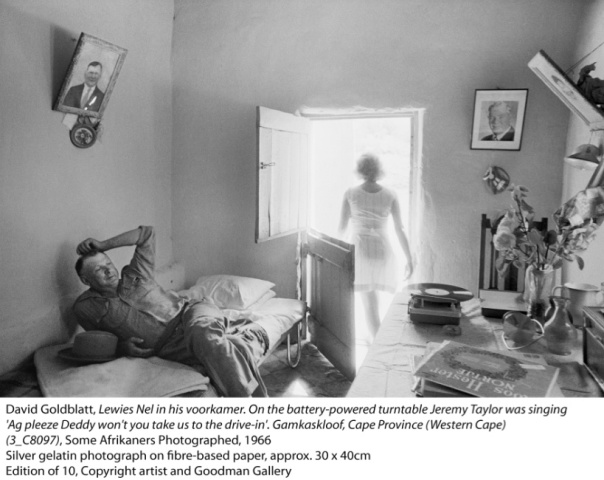

RN: You’ve described Afrikaners as being a highly contradictive people. During the course of your series Some Afrikaners Photographed (shot in the 1960s), do you think you grew to empathize with them?

DG: That’s a complicated question. Yes, I did empathize with them in many instances. But I would say, rather than use the word empathize, that I became aware of complexities and nuances in ways that I hadn’t been before. I hope that the photographic essay Some Afrikaners Photographed reflects my exposure to these previously unexplored cultural differences.

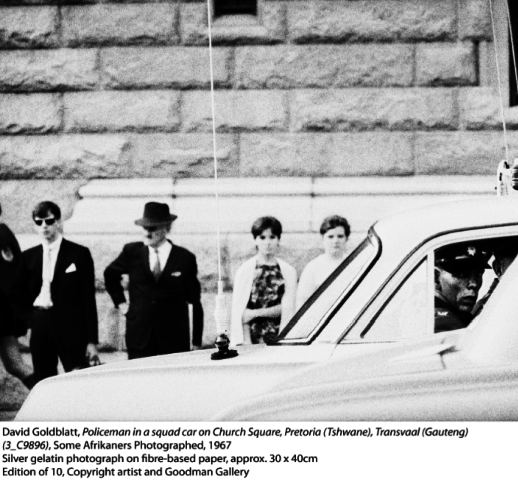

In all of the photographs that I’ve ever taken, I very rarely try to do one-dimensional shots. To me, they’re too easy and they don’t really attempt to deal with the complexities of the real world. For example, in the series you mentioned, there is a photograph that could be viewed as purely one-dimensional. But by understanding the image’s layers it’s likely your perspective would change—making you view Policeman in a squad car on Church Street, Pretoria (Tshwane), Transvaal (Gauteng) (1967) as a far more complex work. I snatched it while standing at a traffic circle in Pretoria. As I was looking through my Leica telescopic lens a squad car jumped into focus in front of me and in the car was a policeman, looking straight at me. His face seemed completely bare. He had what I regarded as a Gestapo face; there was a brutality about him that I couldn’t confront, frankly speaking, he frightened me.

In the background, in the same frame as this police officer, there was a sidewalk full of white people, who were probably waiting for a bus; they appeared as nothing more than grey shapes. I realized afterwards – I can’t claim that I realized this in the instance of taking that photograph – that those grey shapes were us. Those blurred images were the whites of South Africa, sheltering behind the gun of the policeman. And this was the truth of our situation in many ways. We were the privileged group, protected by the guns that belonged to the ruling class, which of course was the national party government.

So it was a complex picture in its own way, but it originated in my instantaneous response to that head in the squad car. Other people may have a different interpretation of that photograph and I would be very glad if they did, because to me, photographs are to be read and peeled away like skins on an onion, so that you have various possible interpretations.

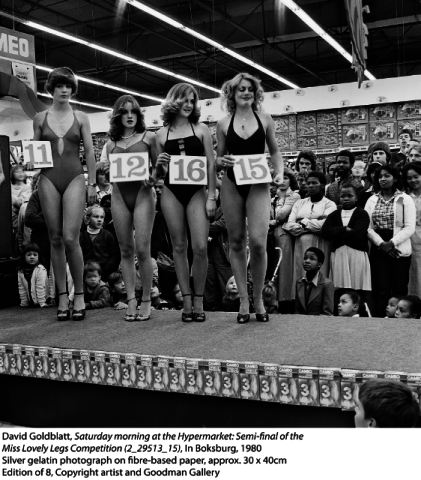

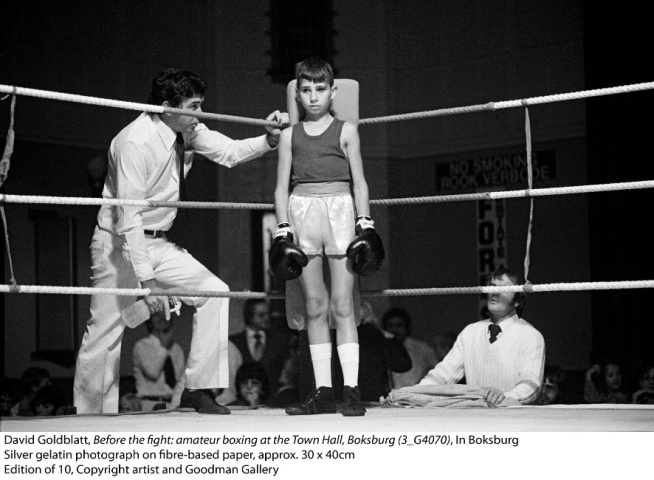

RN: Unlike Some Afrikaners Photographed, in your series In Boksburg (shot in the subsequent two decades) you were capturing the everyday social rituals of the townspeople, in familial and social settings. The town was very similar to Randfontein where you grew up. But despite your determination to present the unordinary, the series has somewhat of a staged feeling. Did you intend for the settings to feel theatrical at all?

DG: That’s really interesting, because none of those photographs were staged, not a single one of them. Let me explain the background to that work. As you described me at the beginning of this interview, I am a middle class White English-speaking Jew and I come from that class. I find it very difficult to photograph my own family. I have photographed my children and grandchildren occasionally, but I’ve never been able to make a pursuit of it. And similarly, for a long time, I avoided photographing the background from which I come, i.e. middle class White South Africa.

I happened to be doing some commercial work in Boksburg, a town near Johannesburg – for a big finance house – when I realized that the city was very similar to Randfontein. It wasn’t exactly the same; it was different in that it seemed far more raw. I won’t go into the complexities of how I chose Boksburg. But I will tell you, it was one of three towns in that area I was considering: Boksburg, Benoni and Brakpan. I was interested in all three locations and though they were categorically similar, Boksburg was the one I eventually focused on. The city possessed a nakedness, which I regarded as being essentially middle class White South African, or at least what was then middle class White South African.

I became absorbed taking photographs in Boksburg. I had in the course of other work, particularly in the black townships of Johannesburg (such as Soweto) and the city’s white suburbs, shot quite a lot of people in their homes. So with this project I wasn’t really looking for intimate portraits of people in private spaces. Gradually, as the project progressed, I realized more and more that I was interested in ordinary daily life in these communities. I wanted to explore the ways in which their normality exhibited in public—the places that even visitors, such as you and I, would be able to see: streets, supermarkets, dance classes, soccer and rugby matches.

Technically, for almost every single photograph I employed a normal 80-mml lens on a 6 x 6 cm format camera, such as a Rolleiflex or Hasselblad, and possibly a few shots with a 35-mml lens. The tonal range was kept quite narrow. Again, I didn’t want to dramatize anything. I didn’t want people to say “what a clever photographer”. I didn’t want them to think that this was photographicness; I wanted them to feel as though they were present at whatever was happening in the exact moment the photograph was taken. So thank you, for giving me a completely different interpretation.

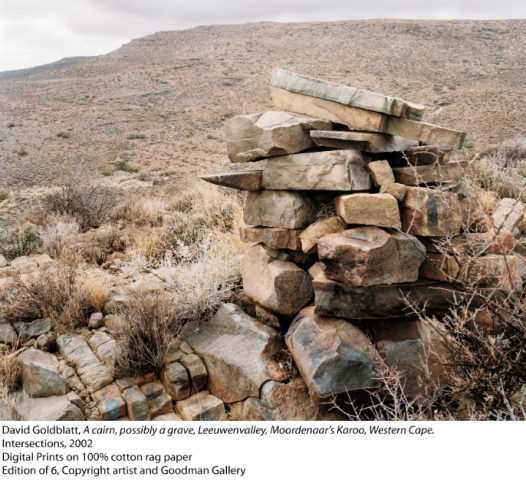

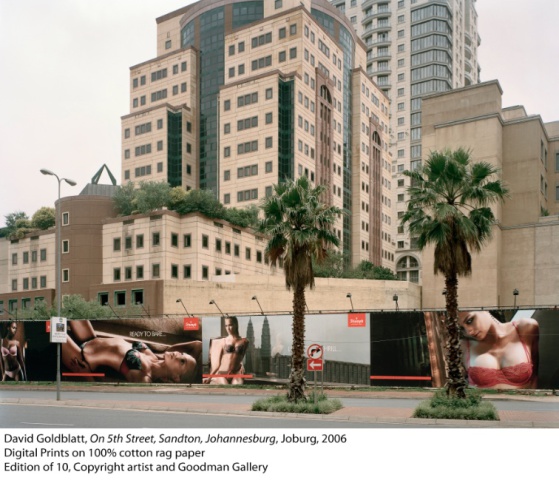

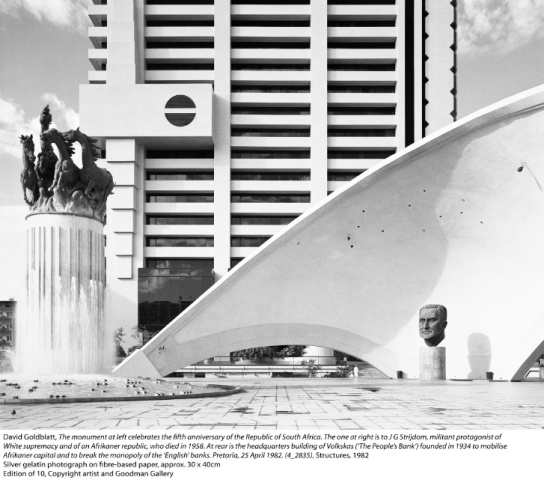

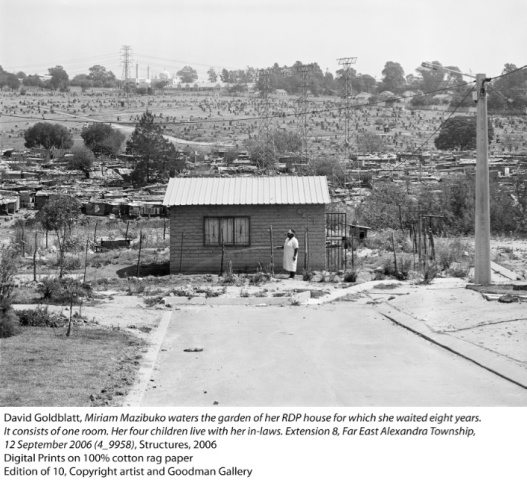

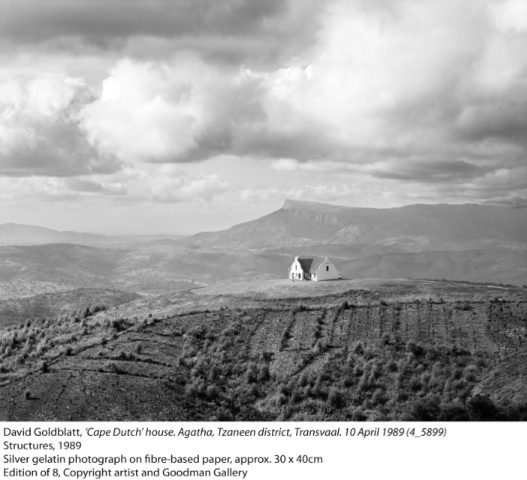

RN: You’ve described the expressions of South Africans as being naked, especially in regards to apartheid. In your series Structures, government buildings and places of worship, can be viewed as expressions of the country’s values or at least the people who built them. Is this ethos manifested mainly in structural elements or do you see it in other aspects of South African culture?

DG: I’ve been working on Structures for about forty years. Let me deal with the last part of your statement first, I think you’ll find in a lot of ways, if you really strip it down to its essentials, my work is concerned with values—at least I hope that’s what you will find. The work I did and am still doing on Structures is an attempt to analyze the things that we build. The structures I am referring to in this case are built by humans. There are also structures built by animals and birds, and though it is possible to look at those structures and analyze them, when you’re dealing with human structures you’re dealing in almost every case with an expression of values.

Let me try to explain, let’s say you form a relationship with a man and you get married. Initially, you each lived with your parents growing up and now you are making a second home together. How do you go about that? What do you do? What is the process that begins to unfold as you gradually reach a conclusion about what will become your home. Let’s say from the beginning he declares a desire for a double storied house, a big garden, and a swimming pool. You have much more modest aims in mind; you realize that as the putative housewife you’re going to be responsible for quite a lot of this structure and you would much rather have a smaller, more compact house, one that is designed to save labor. Plus, you don’t particularly want a swimming pool, because you regard swimming pools as a declaration of values that you don’t sympathize with. Swimming pools suggest consumption. You want a modest garden, you would like to cultivate roses and dahlias, and for that all you need is rich soil and a small space.

So before you start considering divorce, all of these things have to be sorted out. This is what happens in real life—people have to arrive at structures and space themselves. Quite often these partialities differ, unless you’ve come to an understanding of which values are important to him and which values are important to you early on. Your house is an extraordinarily rich book; the structure is a physical declaration of the values that you and your husband share. This same principal can be applied to every structure that we’ve built; included in that, are societies ideological and political structures, which don’t necessarily have to be physical. But because I’m a photographer and my camera can’t easily photograph things that aren’t physical, I photograph structures that I can see. These structures have ranged from the interior of a beehive hut in Zululand in the KwaZulu Natal province to grand statements of power and dominance in the form of religious and governmental constructions.

I find our structures in South Africa to be particularly rich. They are naked in their declaration of values. This is perhaps because we are a young society. We don’t have many structures that are so old that it becomes impossible to know what values initially motivated their construction. And because we are still in a sense, a kind of frontier society, one in which the social contract has not been fully explored and worked out – smoothed out in a hunky dory way if you will – there’s still a great deal of terribly vital differences amongst us. These differences mean that our structures inevitably become major declarations of values. And so, I look at our structures not as architecture, which I am interested in as a field of study, but in this case as a photographer. I wanted to look at structures as a declaration of values. And it became, and still is, a very interesting pursuit.

I spent 15 years on Structures, but suddenly the bottom dropped out—when then President F.W. de Klerk made his famous speech, essentially ending apartheid. And I thought, well, this is the end of it. What am I going to do with all of this? I was going to call the book, The Structure of Things Now, because “now” was a reference to apartheid. Thankfully, I was in America with my friend Ezra Stoller, a great architectural photographer, who told me to simply change it. He suggested I call it The Structure of Things Then. And so I did.

I then discovered, some years later that the project was continuing. South Africa was in a new place, one in which new structures were emerging. So now, I’ve come to call the book, The Structures of Domination or The Structures of Dominance and Democracy. That’s not entirely chronological, because I discovered that within democracy, we have structures of domination. But anyway, it’s a very interesting field, with very rich pickings for a photographer like myself.

Following David’s interview with Arthub, the artist took the time to write to us, so that he could more aptly elaborate on his understanding of values and how they relate to his work. Check out the extended interview for David’s explanation of values—which goes to the core of his photography. The artist also gives us a ‘sneak peak’ into the progress of Structures now and what fans can expect from the series in the future.

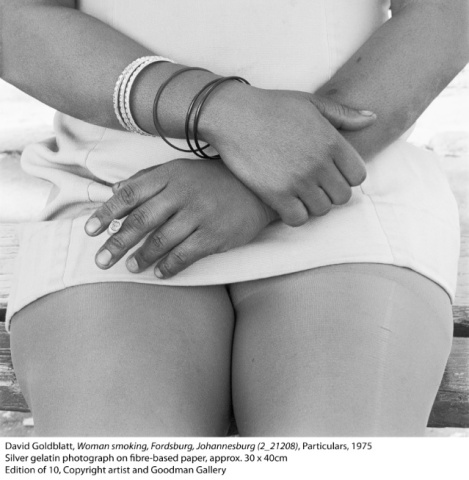

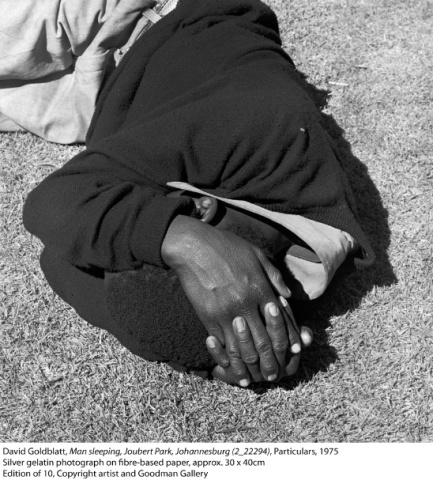

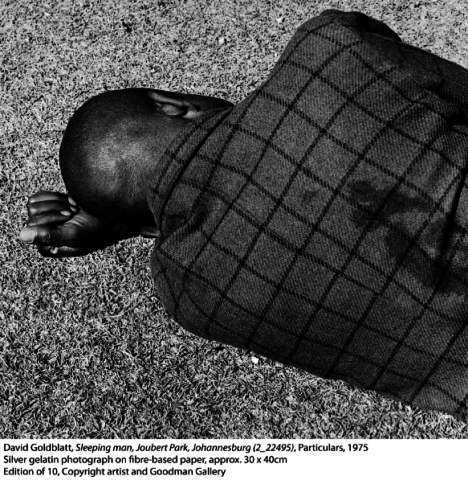

RN: Your series Particulars, which you shot predominantly in 1975 (over a period of 6 months), is especially interesting. It’s very aesthetically different than the rest of your work. You were quoted as saying that you wanted to be more lyrical in the photos from that series. I was wondering if this was a moment for you to break free from the restraints of what you felt like you should be shooting and simply photograph something that you found beautiful?

DG: You are quite correct. Yes, this was something that excited me greatly and for 6 months I was obsessed. It was for me a moment at an attempted lyricism. I was, and am still now, very envious of people like Edward Weston, who never seemed to have a thought about who owned the piece of land he’s photographing and how they acquired it.

This series grew out of the portraits that I was taking during that period. While shooting in Soweto and the white suburbs of Johannesburg I became very conscious of the fact that if a person moved a hand or a leg, or slightly altered their posture, it would have a profound affect on the photograph that I was taking. So I became particularly conscious of their limbs and bodies, breasts, hips, faces – not so much the face that you take a portrait of, but the face as a part of the body.

Exploring that and giving free reign to it was a great pleasure. Initially, I thought it would be a purely sensual / sexual / lyrical exploration, but I soon discovered that politics crept into this series as well.

RN: My last question is also an inquiry about the way you work aesthetically. I know that only recently, and I say recently meaning the last decade or longer, you started using color for the first time in your series Joburg (mid-1960s to 2006) and Intersections (1999-2009). You once said that viewers need to work to look at a black and white photograph, that it doesn’t immediately come to you, whereas with color it’s more sensuous, sweet, and welcoming. Do you still feel that way? Or has your view of color changed through your use of it?

DG: I’m not sure about that. I can’t be dogmatic about the answer. But to me, color does remain a rather sweet medium; it was too sweet during the years of apartheid to use for my personal work. After apartheid, I spent about a decade photographing the country in color and I stand by those pictures. I think they were a personal exploration, like everything else I’ve done. Moreover I enjoyed them and I still enjoy looking at some of them.

But there is no question that for me the black and white photograph is a more complex object. It’s not just that the viewer has to work to understand it, and I’m not sure that I would say that again. Now I would say, that there is certainly a tension in black and white photographs. There is almost no tension when you look at a photograph in color, because it duplicates the world in a way that we all know. Unless there’s been a deliberate falsification of the color, which is a different thing entirely—that’s a more conceptual sort of approach. But generally speaking, in a color photograph you know immediately what the work is about and the color speaks to you directly. In the case of the black and white photographs, you know the content, but at the same time, you don’t know it, because it’s not quite the same as reality, so there is a tension in you, the subject, the viewer, to me that is endemic in the black and white medium. That doesn’t exist in color photographs.

I would like to clarify that I believe that there is a potential tension in black and white photographs, it doesn’t always come, but unlike color photos the possibility for tension is there.

Arthub would like to thank David Goldblatt for not only taking the time to speak with us, but for the photographs he has taken over the last fifty years. Whether or not he believes his work has or will have an impact on the narrative of South Africa, his efforts to identify and express the values of a complex nation deserve admiration. We – the world outside of South Africa – may not always get the joke, but we appreciate his efforts to tell us the story of his nation nonetheless.

For information about David Goldblatt and his work please go to Goodman Gallery or write to: David Goldblatt, Box 46086, Orange Grove, Johannesburg 2119, South Africa.

Arthub’s interview with David was conducted April 1st, 2016 via Skype.

Make sure to check out Arthub’s interview with Roger Ballen launched last week here.