Engaging with South Africa, Part One: Roger Ballen

Arthub’s Director and Founder, Davide Quadrio, had the opportunity to moderate a panel discussion at the 4th edition of the Cape Town Art Fair this past February. The talk, Cross Cultural Encounters, Post Colonialism and Appropriation in the Age of Artistic Mobility, addressed the geopolitics of China’s engagement with Africa, departing from the pivotal 1955 Asia-Africa Conference in Bandung and its cultural agenda.

Davide’s first time in South Africa was visually, mentally and emotionally demanding—he came back equally perplexed and enthralled. The country’s complex historical narrative has undeniable present day social ramifications that will continue to influence the cultural landscape of Cape Town. Understanding the history and social standings of the city’s citizens is difficult for any outsider to comprehend.

In an effort and desire for understanding – curiosity of course being at the root of all artistic undertakings – Davide has selected artists he encountered in Cape Town, both directly and indirectly. As a post-fair analysis Arthub has initiated in-depth interviews with Roger Ballen and David Goldblatt, which will be launched consecutively. Davide found the works of both photographers to be amongst the most striking during his brief, but powerful journey to Africa.

Roger Ballen (b. 1950), one of the most influential photographers of the 21st century, has been living and working in South Africa for over 30 years. He received his first camera at the age of 13 and hasn’t stopped photographing since—the images he creates are as much an analysis of his own psyche, as they are commentary on the world around him. His work as a geologist took him into the countryside of South Africa, but after 1994, Roger began to look closer to home (Johannesburg) for subject matter. He left the countryside – stepping over the threshold of peoples’ homes – in search of more intimate portraits.

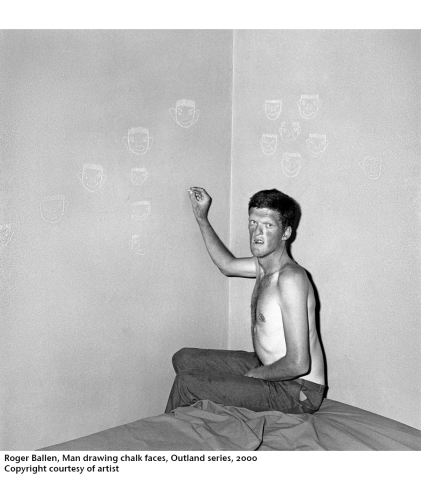

Roger’s simple square formatting and unadorned black and white colors are iconic. Throughout the 1990s a transition from documentary into documentary fiction became evident in his work. Roger became close with a number of individuals he met living on the fringe of African society; these people later became actors in his more recent series. As a student of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley (circa 1970s), it is no surprise that the artist’s works transcend mere aesthetics and instead attempt to intellectually challenge our perceptions of photography and reality itself. With his recent videos Asylum of Birds (2014) and Theatre of the Mind (2016) Roger is creating powerful psychodramas.

Join Arthub’s Head of Production and Assistant Curator Ryan Nuckolls as she speaks with Roger about the continuously blurring line between the fantastical Ballen-world and reality. As the people in his works become scarcer, viewers are left wondering if these hybrid photographs cum drawings cum videos are minimalistic reflections of their own subconscious minds.

Ryan Nuckolls (RN): You once stated that your biggest inspiration was nature itself, can we assume that with your earlier socio-documentary fiction – including Boyhood (1979) and Dorps (1986) – that this is why your photo shoots often took place outdoors?

Roger Ballen (RB): When I said that my biggest inspiration was nature, you have to understand, I think it goes beyond my photography. In this moment, I’m looking at a tree. I’m looking at the sky. I’m looking at my hand. You would have to be really out of touch if you weren’t inspired by the natural wonders surrounding us. But when I talk about inspiration, ultimately I’m questioning the nature of reality itself. Who am I? I want to know how things started.

To answer your question on a more practical level, the real inspiration for what I’ve done has been my ability and drive to take good pictures. I’ve learned the most through my own work. I have always followed my mind and shadow to get to the next step. Many people look outside themselves for motivation, but I’ve always said there’s plenty within each us. The outside is just a function of the inside. For example, I just did a video in Australia and the last thing I said during production was that if there’s no exit from the mind then there’s nothing. If you’re mind doesn’t exist then nothing exists.

In his answer, Roger mentions the shadow state, which is a reoccurring theme throughout his work. Nearly fifty years ago, the artist was exposed to the conceptual ponderings of C. G. Jung, a Swiss psychiatrist and psychotherapist. Jungian psychology defines the shadow as the unconscious aspect of our personalities that the conscious ego refuses to identify, because we have a natural tendency to reject our own undesirable characteristics. Roger’s work confronts this darkness that he believes is suppressed within us all. The insincerity with which society defines normality is brought to light in Roger’s photographs. The darkness we see is a reflection of our own repressed emotions.

RN: You’ve often worked with marginalized characters – including the poor, the mentally ill, and the outliers of South African society – however you have stated time and time again that the focus of your work is and has always been yourself. Your photos are psychological statements, that help you identify that part of yourself you may keep in shadow. So if the purpose was always in some way self-portraiture, what should viewers be able to learn about you when they look at your images? And more importantly, what has the work taught you about yourself; do you see Roger Ballen as somewhat of a societal outlier?

RB: The work should be a personal journey. In my experience, good art should always be a metaphor for the human condition. It’s okay for me to express what I feel and think, but what’s important is my capacity to depict the experiences and feelings of other people in my photographs.

I’ve always said that my biggest inspiration when photographing marginalized people in the late 80s and 90s was Beckett. Of course, from a formal point of view, the nature of his minimalistic theater work is comparable to black and white photography. But it’s the characters in Beckett’s plays – the ones living on the fringe – that I’m interested in. They don’t even try to grasp the nature of reality, because they accept that they are at the mercy of forces beyond their control. So in a way, there’s a truth to their existence, unlike most people living in “rational” society. These people incorrectly believe in their ability to control chaos. Ultimately, these people will lose the battle of control.

RN: In past interviews you’ve mentioned being influenced by the formal compositions of Paul Strand and Walker Evans’ work from the 1980’s. You also stated that the Hungarian-born photographer André Kertész was the first artist who showed you that photography could be art. Could you tell us about contemporary artists that have had an impact on your more recent work?

RB: The artists you mentioned were influential in my youth, but no longer apply to my current practice. Now, if I had to identify an art form that really inspires me I would say Art Brut [a term coined by French artist Jean Dubuffet, which translates as ‘raw art’ and describes works created outside the academic tradition of fine art], including art from Africa or Papua New Guinea. Art of the insane, children’s art to some degree—I don’t really try to distinguish between contemporary, Art Brut and older movements.

If I like it, then I respond to it. Though I understand why it’s done, i.e. financial reasons, I think part of the problem with the art world and modern society in general, is that there’s too much stress on what’s happening now, now, now. Good art is timeless. If it’s purely contemporary it has its day and then it disappears. If you want the truth, I honestly don’t like the word contemporary at all. I like cave art—it’s better than a lot of contemporary works you see now.

RN: What about young artists – do you see anyone in particular challenging the visual language of photography today?

RB: I see a lot of people come and go. I have a foundation that supports young photographers. People join to help expand the public’s understanding of the aesthetics of images.

There are people here or there that take good pictures. But it is impossible to know at the age of twenty-two how far their vision can expand; at that age, you haven’t had a long enough life to reflect back on and work off of. So I wouldn’t try to blow somebody’s trumpet that’s at the beginning or even middle of their career. I think at the end of the day, unless you’re a super genius, what’s important is your artistic career over time. And I can tell you, there are not many geniuses around.

The Roger Ballen Foundation is dedicated to the advancement of education of photography in South Africa. RBF creates support programs of the highest quality to further the understanding and appreciation of the medium, particularly of black and white photography. Through its educational program, the Foundation organizes master classes, lectures and symposiums around the subject of contemporary photography and collecting photography.

RN: Your work exists within a triangle – merging the camera, your imagination and the real world – as your photos continue to blur the lines between reality and fiction, possibly slipping further into an imagined stage, do you still feel that the lens is what continues to ground your work?

RB: Because of its history, people associate photographs with what’s in front of them—the so-called real world. I don’t know what the real world actually is, but nonetheless, that’s the association that photographers are burdened with.

Whereas with painting, when people look at a canvas they tend to perceive it as an imaginary world. I concede that to some degree photographs are depictions of the real world, in that light bounces off of physical spaces and is then being transformed with a digital chip or film. There is something of the material world within these images, but ultimately it’s about the transformation of reality, not only through the lens, but also through the mind. My work inhabits an enigmatic zone between so-called fact and fiction, documentary and the surreal—its existence lays in-between these states of being.

It’s important to respect this line of actuality, because if you go too far to the surreal, then you are in the zone of painting and people don’t believe the work. But, if the work is too documentary then it doesn’t have its own identity. I don’t necessarily try to consciously stay on that line, but its important, and I understand the border between these two forms. Being in this shadow is an important place for me and for the work to be.

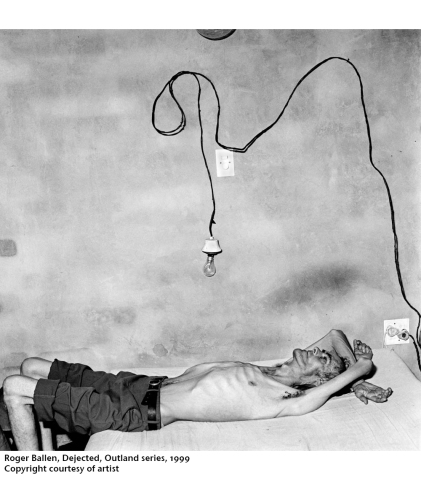

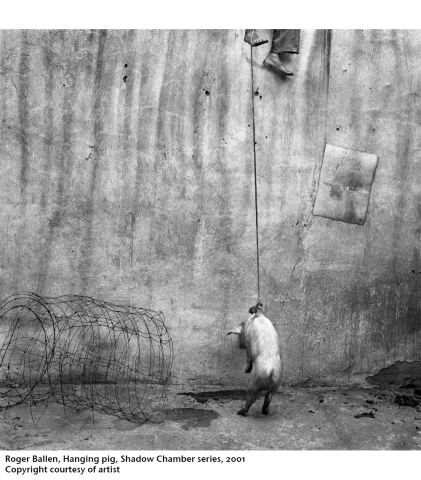

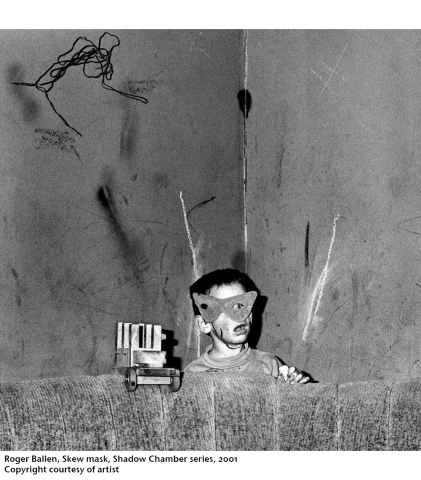

RN: After 2003, with series like Outland (2001) and Shadow Chamber (2005), faces started to disappear from your work, replaced by more theatrical installations with drawings, symbols and signs; when people are included in these scene they often feel like actors helping to craft your psychodramas. This hybrid aesthetic is fascinating, what elements of your previous series do feel remain present in newer works and what elements have you moved on from?

RB: Portraiture definitely disappears, as well as anything related to socio-economic and cultural issues. These features are replaced by something I would like to refer to – without sounding arrogant – as a style called Ballenesque. In order for people to identify with my photographs I’ve developed my own method for transforming the world. I integrate paintings, drawings and installations into one frame, while still adhering to the black and white aesthetic I’ve used my entire career.

Since the early 2000s, a lot of artists have jumped into photography; they take pictures of installations and manufacture prefabricated scenes, but their pictures don’t have an inherent impact on viewers, because these people don’t actually understand photography. In my work, I’m able to reimagine various medias because I have fifty years of photographic experience. I understand how the content of the frame will affect viewers. I am able to create a world that people believe in, rather than having to explain in endless pages of artistic philosophy what it is I’m trying to do.

I believe the images I make should enter viewers’ brains and affect them faster than they can even open their mouths. The best pictures are the ones you don’t have words for, the ones that leave you in a state of silence. That’s my philosophy about photography and art in general. Art is electric—the works should radiate like highly charged currents.

RN: In the introduction of Shadow Chamber, Robert A. Sobieszek wrote: “To discern fact from fiction in Roger’s work may be simply impossible; to tell acting from real life may also be; to bother with such discernment may not be only futile but missing the point.” You’ve often said that describing your photos in words is nearly impossible. Have you truly succeeded when viewers walk away without being able to verbalize the impact of your work, yet still being haunted by them?

RB: If you can verbalize the meaning of the picture then it’s probably a bad picture. An ability to articulate the work means fundamentally that the mind comprehends it. This comprehension is a bad thing. Its like a virus that gets into your system, if the body has no understanding of the virus then it can take over and makes you sick, but if the body understands the virus then it kills it. It’s the same with photography; the mind shouldn’t build up a defense mechanism against the picture.

You can’t just go out and create the kind of images I’m talking about here. Nine out of ten pictures won’t have this affect on people. They walk away without anything. Like a virus, strong photographs are the ones that are able to enter the mind, because the mind doesn’t know how to fathom what’s before it.

RN: At a certain point in your work, you started to portray the essence of the places you were shooting—questioning what elements made South Africa so aesthetically different than the rest of the world. Is it true that you’re no longer shooting outside of Africa? Is it because within the borders of your adopted nation you have enough source material to last a lifetime?

RB: I stopped shooting outside of Africa in 1982. I don’t even bring my camera when I travel, I don’t need to. I just take my phone. A fellow photographer recently told me they didn’t know where to go for inspiration. I told them there’s only one place to go—it’s in your mind. Your mind is the answer. There are plenty of places to explore within yourself; you just have to figure out how to get there.

It’s all about imagination. If I can’t take a good picture there’s nobody to blame except myself. Photography is about transformation and perception. Does a philosopher or poet have to travel to Timbuktu to fulfill their goals? No, everything they need is within them. For eight hours every night you have the opportunity to explore uninterrupted the depths of your own mind.

When I was younger, I traveled the world for years; that was my modus operandi. My state of being required me to travel. But now, these inner demands for adventure are no longer practical, nor necessary. As time moves on we adapt. You find new ways to explore and create. You can’t blame anybody but yourself for your own failures.

Nobody can take pictures like me. If you’ve seen my videos, it may seem like South Africa is an awful, horrible, crazy place, but the place before you is the Roger Ballen world. The camera for a photographer is like a paintbrush to a painter or a pen to a poet. The world perceives the camera as an objectifier. I see it as a transformer.

RN: Like Stanley and Stefanus, you tend to work with reoccurring people in your series. Do you have many ongoing relationships that have developed during your time in the Outland?

RB: As we’ve been speaking you’ve probably heard my phone buzz at least ten times. Those calls were most likely from ten different people, whom I’ve been working with over the last twenty years. It would be impossible for me not to develop long-term relationships with the people in my pictures; some of them I see more than others, some die, some disappear, some I actively keep in touch with. Sometimes these people reappear in the work, but often they don’t. You become invested in the people you work with. For example, I know someone who has just passed away. They want me to pay for the funerary costs; you would be surprised how often I receive requests like this. The constant contact is endless, all day and all night people reach out to me.

RN: Is Outland an Afrikaans word or is it an expression you created?

RB: Outland is not an Afrikaans word nor is it derived from the Afrikaans word ‘Uitlander’. I created the expression to denote places on the edge of society.

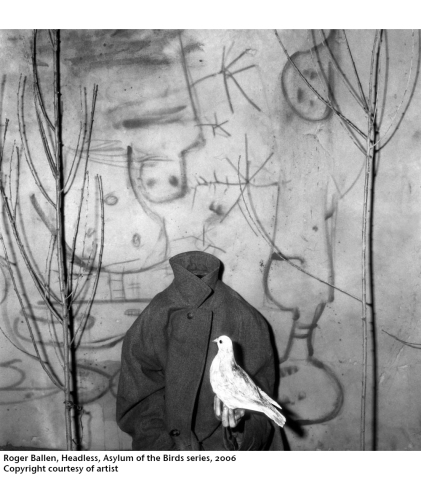

RN: You found the location for Asylum of the Birds while you were working on Shadow Chamber. Did someone suggest the location in Johannesburg or did you stumble upon it? The house is a perfect match for your work: society’s outcastes living a transient existence in a home that could be described as “dark”, with animals and birds all around them.

RB: Actually, during the shooting of Shadow Chamber some of the people in the building there, had stayed in the Asylum. They took me to see it.

I’ve always been interested in animals; for many years, the relationship between the human psyche and the animal psyche has been a thread throughout my work. The fact that the animals and humans in Asylum were living in such close proximity to each other enabled me to create metaphors that I wouldn’t be able to in most other places.

The images in Roger’s monograph were shot entirely within the confines of a suburban house in Johannesburg, the location of which has remained a tightly guarded secret. To mark his new publication, Roger worked with director Ben Crossman to produce a psychologically powerful film that follows the artist into a world synonymous with his photographs, as never before seen on film. Watch Asylum of the Birds here.

RN: You’ve said that when shooting Asylum the nervous energy of the birds made the photos better—do you think this idea exists in various manifestations during your shoots? Does working in more organic settings, outside traditional studio spaces, allow for unpredictability?

RB: This is an important point to address. I think photography by its very nature is most effective when people perceive images as decisive moments, a special instance that cannot be repeated. This quality of photography has been influenced by the philosophy of artists like Cartier-Bresson. Having grown up as a street photographer in the 60s and 70s this essence of imagery has greatly impacted my work. I evolved from a black and white street photographer into an artist.

This concept of the moment has always been a crucial element within my pictures. The fact that the birds were nervous and moved around a lot is what created the opportunity to make impactful pictures. There are a lot of photos in this album that depended on the movement of the birds in 1/500th of a second. This method of production is unbeatable. In a lot of the photographs the birds are flying at high speeds, but still I got the picture. The pictures are good because I was able to capture these precise and fleeting moments. If you took that movement away, then it would just be another installation shot, like we see too many artists using today.

This movement through time is an essential part of taking good pictures. People don’t understand how hard this is to achieve—many photographers will never reach this point. It’s easy to create an installation in which you can safely test out your ideas, but you have to push the boundaries of photography in order to figure out how to take your work to the next level. The impact of your pictures depends on your ability to capture an authentic moment that cannot be repeated by anyone else.

RN: Your series often take years to configure, can we assume that the aesthetic of the work normally changes during this process or does the instigating image that sparked the entire compilation remain present throughout its entirety?

RB: Each series usually takes five to six years. In the beginning, I have no clue in which direction the work will develop, because the initial idea can’t be verbalized, it’s very process oriented. It’s like a sculptor taking a piece of clay—the sculpture comes as you mold it. The artist continues to make smaller, refined movements to get more detail from the amorphous material. The vision becomes defined during the process of creation.

What I usually find in most of my books is that for each series I go through distinctive periods. One book – may be about birds – but if you start to cluster the pictures by dates you can identify similarities between the works. As time moves on, the pictures metamorphose.

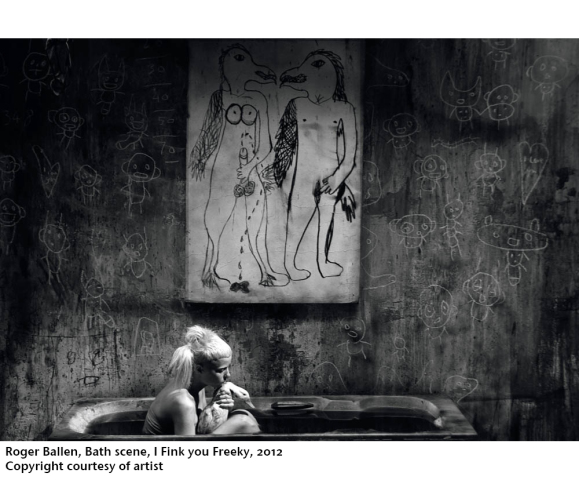

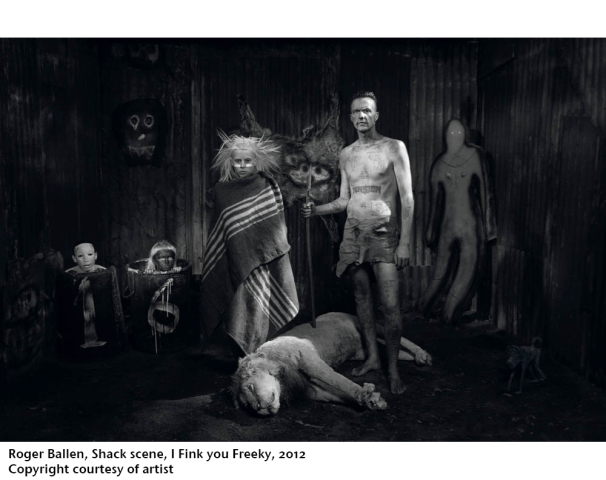

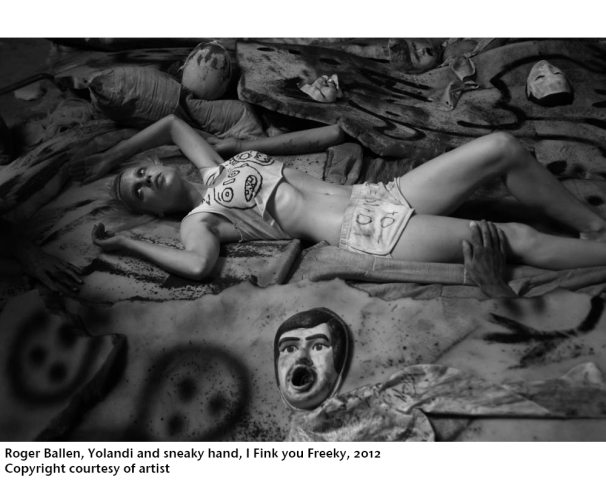

RN: Ninja and Yolandi first reached out to you in 2005, but it was several years before you initiated a collaborative production. The rap-rave group claims to have been so influenced by your aesthetic that in fact Die Antwoord was born entirely from your artistic identity. In what ways did your method of creation differ during production or was it truly a symbiotic cooperation? Are you just as happy with the music video as with the photographic publication that resulted from this co-production, or do you feel that the photographs are more indicative of your work as an artist?

RB: When the duo first contacted me in 2005 they said when they saw my work they gave up who they were. They found my work so inspiring that they took a year to reinvent their musical identity.

We discussed the possibility of cooperation for a long time. Before 2011, when we finally decided to do something together, they had already integrated some of my work into their performances. We decided to co-produce the music video I Fink u Freeky (2013), which took 5 days to shoot. I really didn’t have any expectations going in, because I had never worked on a music video before. I did all the installations for the movie and acted as co-director.

The success of the music video was mind blowing. Today we have nearly 80 million hits, which has certainly helped expand my artistic outreach to a lot of people that may not have seen my photographs, if it had not been for Ninja and Yolandi.

Aside from having millions of people see my name and work (which was of course gratifying), the most important thing that came out of my collaboration with Die Antwoord was realizing the power of videos in modern day society. I started making my own videos—not as advertisements for my photographs, but as a parallel art form.

In a previous interview Roger stated that, “people are innately affected by music and more quickly affected by it than by photography. Music is almost animalistic in its capacity of getting people to forget who they are. I Fink u Freeky is a testament to the power of music, of media, and of the way people relate to music. It is different in a real way. The video had some deeper meanings, both funny and serious, and people could relate to it on different levels without having to stretch their minds.” Watch the music video co-produced by Roger Ballen and Die Antwoord here.

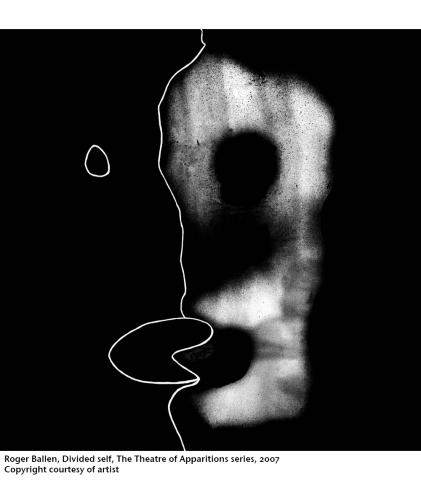

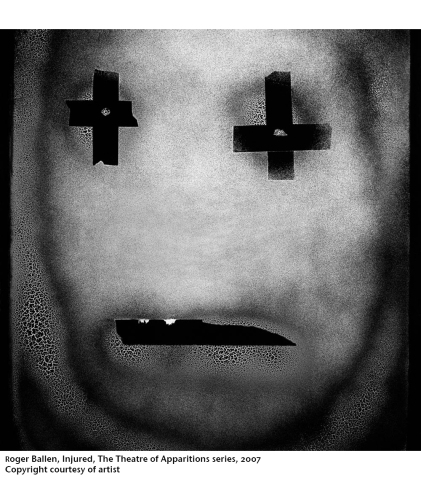

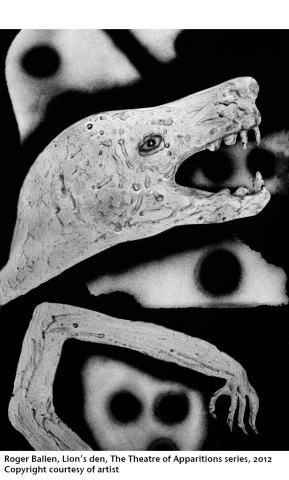

RN: In your latest series The Theatre of Apparitions (to be published by Thames and Hudson in September, 2016), you are blurring the boundaries between photography, painting and drawing more than ever before. In your new technique you paint and draw directly on glass, in fact, to be more accurate, you paint the surface and then carve away to allow natural light to come through. The work is then illuminated from behind and photographed. The result is quite powerful; viewers are confronted with these vaporous otherworldly glyph-like images. Can we consider these photographs as yet another portrayed variation of the shadow aspect—an ever-present theme in your work?

RB: I think all of my photographs represent the shadow side of the human psyche in one way or another. These images reveal an aspect of the mind that goes very deep; a place that most people are out of touch with. If we define the shadow side as a place that we are out of touch with or scared to enter, then the photographs from my upcoming series The Theatre of Apparitions certainly fits that definition.

I’ve been working on this series for eight years. The pictures are very different than anything else in photography right now. The drawings feel like pictures of ghosts. The series will be coming out in print this September. I believe “The Theater of Apparitions” is a very powerful book that will be accessible to those with little understanding of photography, ranging to my more sophisticated viewers. I’m very excited about this new work, because I think it’s a really big step away from anything else I’ve done before.

RN: As the work becomes more abstracted do you feel that you’re still straddling the line between documentary and the surreal or have you abandoned the “real world” for the Roger Ballen world entirely?

RB: This is a very good question. Photography is generally dependent on transforming the physical world. Consequently my photographs are likely to straddle the documentary and surreal, yet the world that is ultimately revealed in the transformed reality of the photographs can best be defined as Ballenesque. It is almost certain, that this process will continue to expand in different directions.

Roger has just finished a new video in Sydney—a work that will undoubtedly haunt viewers. It was produced in the dungeons of a previous insane asylum. Check out the artist’s latest work here:

Copyright courtesy of artist

Arthub would like to thank Roger for not only speaking with us, but also sharing his photographs and videos. We hope that in supporting his work we can encourage a stronger link between China and South Africa. The artist first visited Shanghai in 1986; he did not return until last year, on the occasion of Photo Shanghai. Arthub hopes to welcome Mr. Ballen back again soon.