UK Exhibition: China! China! China!!!

China! China! China!!! is a major exhibition which features 15 contemporary Chinese artists whose work has not been constrained by the rapid expansion in demand for Chinese art in recent years. The exhibition opens at the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, University of East Anglia, Norwich, on Tuesday the 10th of February and runs until Sunday the 3rd of May, 2009.

“We are delighted to be bringing China! China! China!!! to the UK this spring. After a period when China has been the constant focus of international attention, we are keen to reflect on the impact of this interest, and to offer a thought provoking show which does not simply feature artists whose work is in high demand in the West at present,” Amanda Geitner, Head of Exhibitions, Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts.

China! China! China!!! has been organised by the Centro di Cultura Contemporanea Strozzina at Palazzo Strozzi in Florence and is comprised of three distinct projects created by cutting-edge China-based curators: Li Zhenhua, founder of the Art Lab, Beijing; Zhang Wei, Director of Vitamin Creative Space, Guangzhou (on the Pearl River Delta, north west of Hong Kong); Davide Quadrio, founder of BizArt in Shanghai.

The artists have produced work that is radical, critical and often playful, which is rooted in his or her local context, but also participates in the international art arena. The result is a collection of fascinating and uncompromising works that give new depth to our understanding of what it means to live in a society going through immense change.

Projects Presented at the China! China! China!!! Exhibition in Norwich

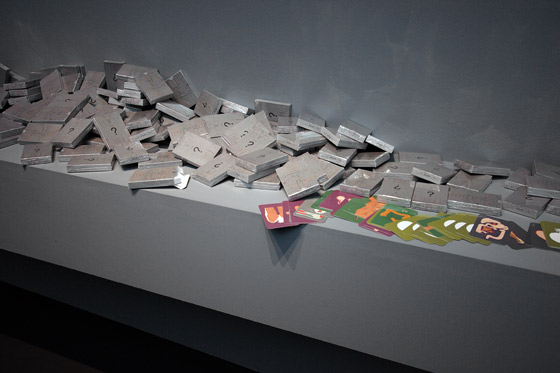

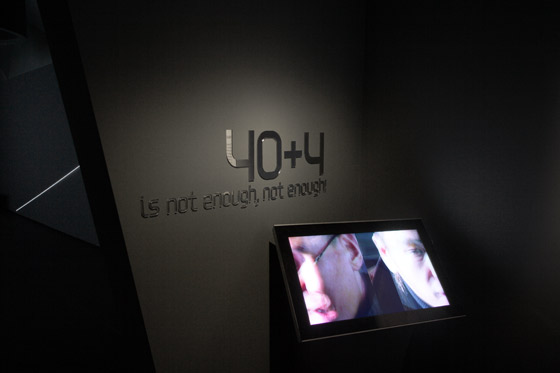

Davide Quadrio’s 40 + 4 Art is not enough, not enough! is a documentary mapping the complex reality of Shanghai’s artistic scene and reflects on the social relevance of contemporary art in the China of today. Quadrio interviewed 40 of the city’s major artists, asking a series of questions that were grouped by theme on a deck of cards. Themes discussed include the importance of the artist in modern Chinese society, the artist’s relationship with the public and the influence of the international art market on artistic production.

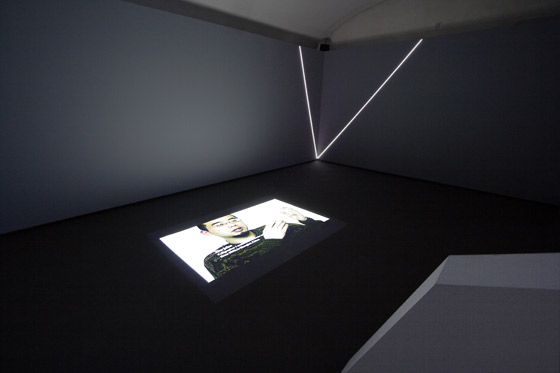

Li Zhenhua presented, Multi Archaeology, 1162 – 2162 Another Thousand Years. The theme of Li Zhenhua’s curatorial work is the search for common cultural roots between different populations, both between China and its neighbours and East and West. In Multi-Archaeology, Li Zhenhua and artists Ren Qinga, Wu Ershan, Shen Shaomin and Zhao Liang examine cultural identity, demonstrating how individuals are moulded by constant change. The figure of Genghis Khan, founder of the Mongol Empire, is used as the symbol for communication between civilisations.

Zhang Wei, in Throwing Dice has selected works that provide an individual response to China’s rapidly changing social and cultural world. Duan Jianyu’s Art Chickens sit in front of watercolours of Chinese landscapes, Cao Fei (aka China Tracey) explores the lonely on-line world of Second Life in her film I-Mirror and Chu Yun’s photographic work Career documents government officials in their private time.

China is waiting: the year 2008 downturn

After the recent mania for Chinese Contemporary art, the financial downturn is taking the art market as well. In only three months, the fall in the market for Chinese contemporary art was so severe that many newly established galleries, (and those without visions or a strong commitment to Chinese practice), are closing down, or reducing their activities and investments. The time of easy money has gone.

In the last five years–the ‘golden wave’ of Chinese contemporary art–we watched the enormous increase in art-investment in China. Art was treated as a product with particularly high investment returns. The speculative market in China was created largely by western collectors and not primarily by the local market. The Asian collectors were a small minority (even though some of them were extremely important) coming from Beijing and Shanghai, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Singapore.

In the project presented in China! China! China!!!, 40+4, Art is not enough, not enough!, one of the artists Zhu Julan, described the situation in 2007 as follows:

I think art itself is luxury. Of course luxury can exist in either the material dimension or spiritual dimension. What I am talking about is more on the spiritual dimension. If you have the ability to enjoy art, it means your life is very luxurious. It requires a lot of knowledge, artistic accomplishment and emotional investment.

From another angle, art has its commercial value. It is very expensive, so we call it luxury. Of course there are lots of good art works which truly are luxury items. They are very expensive things. But we still have to distinguish between the two. That is, even if I have no money, I can still enjoy art; but even if I have money, I may not necessarily be able to enjoy art.

More and more artists, when asked about this situation, feel that this moment will facilitate the elimination of a certain group of speculators and ‘trendy’ artists and, surely, will leave space for the good artists to have the time and space to make work. We are now at a crossing point, where the crisis will bring perspective: it is time to become serious, consider curatorial work in the territory, and build a healthy artistic and cultural environment.

There is a long legacy of art in China made without commercial aim–from the revolutionary Star Group in the 1970’s, to those involved in the 1985 New Wave movement and the artists that in the 1990’s lived together at Yuan Ming Yuan village (Old Summer Palace) to work in a community as a statement for art and freedom. The development in the art market from 2005 is a recent phenomenon–what interests us is the relationship between art, contemporary society and the legacy of the last 30 years. If up to now ‘risk’ was the key-word in the art-world, now we need a more in depth analyses of contemporary art in China; only with this attitude can art in China develop and be truly supported.

And for us, our practice continues and moves on. Davide Quadrio is now based in Bangkok, working with a broader Asian network through Arthub. Li Zhenhua’s work is largely experimental and digital-media based. International in nature, his projects continue to engage with artists outside the machinations of the art market. He continues to work in Beijing, but is now also based in Zurich. For Zhang Wei, the work of Vitamin Creative Space continues and she has recently opened an experimental space in Beijing called The Shop. This space is going to open up another platform for communication and innovation in the contemporary art.

The Direction of Art in an Era of Collapsing Values

— a response to 40+4’s interviews

January 2008, Shanghai

written by Zhao Chuan

Section One

This article is a response to a series of interviews with 40 artists planned and carried out by Davide Quadrio (Le Dadou). (These interviews will be referred to as “the interviews” throughout the rest of the article.) The questions in these interviews covered the artists’ personal experiences, their general views on art, how they see the relationship between art and other aspects of society—such as politics, ethics, culture, and so on—as well as their understandings of art’s encounter with commerce. Some questions inclined to the spiritual plane, such as, “Do you find it necessary that a creative/artistic person have a belief? Do you have a belief?” Some others were entirely practical: “Do you find it agreeable to share your money with your gallery?” I gained an initial impression of these artists’ views by reading through transcripts of all of the interviews. From this impression, I returned to the transcripts in search of examples, and then began to elaborate on them.

Most of these artists live in Shanghai. Many of them have had an important place in and influence over the evolution of art in China over the last 30 years, while some others are new blood behind the current direction of contemporary Chinese art. These forty artists are forty living individuals with extremely strong expressive desires. In the mainland’s dramatically changing social environment, they all have different experiences, different personalities and different artistic directions, producing a vista that is is hard to apprehend at a glance or sum up in a word. I am not doing a statistical analysis here. Given the space available and in my own limited abilities, it would be impossible for me to weigh all of these questions and answers. Even my rough impressions touched upon many levels and led in many directions, so that later, in the course of writing, I allowed some impressions to act as reference points for the discussion. These, joined with my own observations and reflections in the past, form this article’s path of inquiry. As I dug into these questions, I was also digging into and making sense of my own self. Clearly, this method does not systematically address each and every question, but I hope the people involved will understand it as an attempt at positive discussion.

Section Two

“If we are to change our world view, images have to change. The artist now has a very important job to do. He’s not a little peripheral figure entertaining rich people, he’s really needed.”

This is a quote from David Hockney. At the end of every interview, each artist had to pick a card on the back of which was a quote by a famous person, and give his or her opinion. This is one of the quotes. Of the forty artists, only one very famous artist living overseas picked this card, but he didn’t expand much on the quote. I read through all of the other interviews, and no one else picked this card. It is as if this topic just slipped through.

The way an artist looks at his or her work is more or less determined by how he or she looks at the world. In the China of 20 or 30 years ago, this kind of question would have been called a question of principle. The question about belief raised in the interviews might be taken as an important starting point for extending this sort of consideration. Other questions in the interviews concerned culture, morality, politics, power, cultural history, intellectual history, social responsibility, art’s contribution to society, and so on. As I see it, the answers to the question about belief presaged the answers that many people gave to these sorts of questions. Davide Quadrio later told me that after the interviews, 70% to 80% of the artists said that they had never thought much about these issues. My overall impression from reading the interviews is that these questions about ideology did not manage to reflect any sort of world view, even though many of the interviewees do not necessarily hold postmodern ideas! Truly, we live in a very different world today.

When asked what his “belief” was, a longstanding and influential artist who has taken part in many international exhibitions replied, “Maybe it’s that there is something I aspire to. Every artist has his own aspirations. Of course, your average person has his own aspirations, too… More practically speaking, it is a wish that people have.” But the problem is that there are so many wishes in our lives. The question I want to pursue is: isn’t a belief the sort of pillar that holds up a person’s mental world, without which that world would collapse?

When interviewed, an upcoming young artist born in the early 1980’s said, “Right now, my belief is that I approve of my own life.” This statement shows an honest attitude toward life, but it also seems to be saying that acceptance of his own attitude toward life is enough to support his inner world.

You should note that these interviews are about the inner worlds of a group of artists who are dedicated to creation. But in their generation, many people use this sort of trivial secularism to express their view of art and life. This sort of trivial secularism has disdain even for naturalism’s search for a common nature. They just dig up the more casual snippets and omnipresent accidents close at hand. Their perverse wallowing in such trivial realist scum, and the emptiness of their attitude toward history, has made them pervasively lacking in or disdainful of the pursuit of rational intellectual qualities.

Two other active and influential artists, born respectively in the 1960’s and the 1970’s, both answered this question in the negative. The first said that he had no creative ability himself, and therefore no belief. The second said that he had never thought about it. The unspoken implication is that talking about this is a waste of time. Put together with their words and behavior throughout the rest of the interviews, their answers were either vacuous or arrogant and contemptuous. Their utilitarian approach to art and jaded attitude toward the art world have variously made them extremely fond of clever devices or drawn them into anti-intellectualism.

We want to determine the facts, whether we find reflection or an utter lack of reflection. What we see in these interviews is that no matter whether they grew up or were born in in the 60’s, 70’s or 80’s, the reactions of most of these artists—about 70% or 80% of them—to “belief” type questions were not concrete at all. Some of them said that they had some beliefs, yet were unable to clearly describe or explain them. Among young artists, there was even more ignorance or vacuousness. Even when some of them did mention belief or religion, most of them did so in a tone that showed little trace of religious feeling. Almost no one went on to touch upon a discussion of world view as a result of these questions and answers. To many artists, belief seemed either an illusion or a casual and extremely individual matter of temperament.

Aside from this, it was very common to have a confused understanding of ethical questions as well as the system of intellectual production and the value of artwork.

Originally, Postmodernism was intended as a theoretical critique of the status quo. When did it become such troubled waters? I think that the ability to answer these questions is not something that can be covered up by sitting around cross-legged tossing out phrases like “freedom,” “diversity” or “reflecting different levels of understanding.”

More than half of the people interviewed strike one neither as craftsmen, nor as intellectuals. Overall, the intellectual level and accumulated learning they conveyed was disappointing. Their speech and the views they displayed during the interviews were coarse and casual, and they lacked elementary knowledge about their own artistic terminology.

When asked about the relationship between art and culture, one artist—who claimed to be studying for a doctorate and serving as president of a university-level art school—provided an answer that verged on the ridiculous: “I think it’s very simple: art plus culture equals art culture.”

Another artist replied, “I think the arts and culture are the same thing… Of course, they can’t be identical… They’re mixed together… Art is part of culture. It’s under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Culture.”

I do not want to imply that there is a standard answer to these questions, nor do I think that artists are bad at expressing themselves, or that they have been affected by their sensory mode of visual creation. Some of them are fond of tossing around esoteric phrases, like to put on airs or affect a certain brilliance, and have a wondrous combination of slick and smug that emanates from their very bones. But most of them are modest and unaffected people with whom one can communicate and have an exchange. Of these people, at least half teach or have taught in art academies. It is quite the norm in the industry for artists who use the creative methods of contemporary art to employ some philosophical, sociological or psychological concepts. I think that their linguistic ability is quite sufficient to clarify how clear or unclear they are about a certain issue. Therefore, when a young artist of their students’ generation, still learning to interpret paintings, says that art is diverse and ideas are boring, or when another young installation artist tries to say that his ethical standard is to not violate the law… well, one can hardly be surprised.

If we take these interviews as a starting point and look at the Chinese contemporary art circle—so fond of using “challenge” and “explore” to explain its work—we find that its intellectual world is in fact weak and disordered. On the other hand, in their answers almost all of them were quite united in their sincere approval of business. Their answers were irrefutably respectful of current business practices. Similarly, when asked whether an artist is corruptible, their answers were basically unable to rise above the level of material desire. Could it be that our thriving bureaucratic market economy, our serious corruption and our towns covered in brothels and bathhouses have limited these artists ability to imagine or comprehend?

Some of the questions in the interviews are themselves open to question, or hint at the same reality. The interviews do not cover the artists’ views on technique or training. Since when is art in this country based on groundless hearsay? And in questions about the relationship between ethics and art, there was often a suggestion that ethics be seen as a constraint, and there was no recognition that ethics might be a fundamental necessity in the long human pursuit of goodness and excellence. Since when has it been true that “art’s purpose is actually to break ethical standards?” This idea turns its back on the relationship between man and art in China’s longer historical context.

Section Three

Let us return to David Hockney’s easily understood quote. It includes some of the most basic concepts in the development of contemporary art: change, world view, commitment, not pandering, wealthy patrons, the outsider, being needed by society, and so on. That remark gave me the idea that if I started out from there it might help me clear away my various dissatisfactions with these interviews, and explain how some of these problems are connected at a deeper level, allowing me to get closer to the plight of contemporary artists.

Even if I didn’t know the original context of David Hockney’s remark, the text makes it clear enough that he takes it for granted that “to change our world view” is a proper and desirable pursuit. Therefore, if our artists don’t think that their understanding of the world is in need of change, then going on to talk about changing world views and the responsibility of the artist just makes no logical sense.

But let’s set aside the course that contemporary art has forged in the West over the last century. Let’s set aside all the blind promises about social responsibility it made during the radical years. That is to say, let’s set aside the context for David Hockney’s statement, even though it might help explain why it is proper “to change our world view.” Let’s just take his words completely out of context and draw them directly into the experience of Chinese society.

Whether we look at it over the course of the last 100 years or the last 50 years, it is obvious that this formulation is neither strange nor awkward to us. On this point, at least, China’s experience has not diverged from that of the rest of the world. Furthermore, we can see that Chinese society’s past 100 years of intellectual exploration, cultural discussion and social projects have been rigorously involved in either proactively or reactively changing our world view.

Not only that, in the original English, Hockney’s phrase “to change” has an active flavor, and for that reason was translated as “transform” on the interview card─giving a clear sense of direction to the act of altering one’s understanding of the world. Transformative actions move in a constructive direction, they tend toward the good, that is, towards allowing a more complete understanding.

“To transform the world” has been one of the most important and vivid social concepts in China for almost 100 years, even though it has been forced to leave its former pursuit of oneness with nature, and evolve towards this kind of unnatural self improvement.

From a visual perspective, the scientific view of the world—such as imagining the world through Western globes and new-style maps—transformed Chinese intellectuals’ understanding of “the world,” beginning in the late Qing dynasty the world was no longer a matter of “between the seas, all are subjects of the king.” This led to the May 4th intellectuals’ worship of science and democracy.

Mao Zedong’s 1942 Talk at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art is an example of trying to use an ideal world view to shape one’s visual perspective. Mao Zedong’s attitude is plain for all to see: art and culture are the nuts and bolts of revolution. David Hockney’s statement shows a willingness to follow such an attitude.

As far as the the visual act of seeing and one’s view of the world are concerned, the construction “to change x, y must change” implies that changing the first cannot be anything but an instrument for bringing about a change in the second. In socialist countries there was a time when this instrumental theory was pushed to the extreme.

In the course of Chinese artists’ active transformation of their visual perspective, experienced together with its society, the 1985 New Wave Movement was an evolution in their view of the meaning of the world. It was the visual implementation of an attempt at reform from within of a value system that rejected profound reflection. Later, in the wake of 1989’s June Fourth Incident, it became the first step in a march towards fragmented values. After the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Iron Curtain that had stood between the two camps of communism and capitalism,when the Western art environment began to transform Chinese art during the 1990’s it seemed even more like an external impetus, carrying a vague sense that it was meant to reform us ourselves. As with two fighters in the ring, when one side gives up, it doesn’t mean that the other side also hangs up his gloves and goes home. It’s just that for the moment we were following the wishes of capital, gradually allowing the market to clear a path. So, working from the inside out, a new visual perspective effectively brought about such a gradual transformation.

I think that how we see the world, what we think the world is, and our understanding of the world are all formed by and integrated with our visual perspective. Another way of putting it is that you only have to turn on the television, open the newspaper or walk out onto the street, and you will see the great vista of Chinese society aspiring to the West in search of a quick buck. In some people’s view, this is the outcome of almost twenty years during which interest groups have forcibly shelved any discussion of ideological questions and purposely blurred questions of world view for the sake of economic development, even hoping that these doubts would disappear from society’s thought. Or it might be that in China’s special environment the Western postmodern wave, which has gained entrance by a variety of routes, has dispelled thinking about the world from the younger generation’s mind.

We could talk about the causes in a variety of ways, but that is not the thrust of this discussion. So, for today’s Chinese artists, the question of transforming the world has neither been solved nor superseded, but seems to have long ago been outdated, shattered, watered down and abandoned. Perhaps ignorance and vacuousness are precisely the face it shows us now that it has gone underground.

I must say though, that placed among the widespread conditions that these interviews have exposed, David Hockney’s statement is a mockery of that face. Even though the one artist who picked Hockney’s quote in the interview responded with disdain, criticizing Hockney for hypocritically painting for rich clients all the time, he too loves being one of the elite, pouring money into expensive installations. Maybe another way of putting it is to say, this unexplored question is simply not the way that this generation cares about or discusses the world now. In any case, I am just borrowing this quote. Just treat it as a reference, a look back at the past.

Clearly, an unfamiliarity with this topic itself, a lack of awareness, has created a split with Chinese society’s past thinking and experience of struggle. Such an outcome can only create a mentally handicapped generation that thinks it is open and self-sufficient, but in reality is just running in circles, trapped within its own narrow experience and refusal to examine history. What is this generation’s way of caring about and discussing the world? The measure by which we are truly evaluated, is precisely the standards we throw away and the idols we erect in the course of our development. They are the picture of Chinese contemporary art that has already emerged, and is included in these interviews.

Section Four

In the grammar of contemporary art, rational thought carries far more weight than trust in sensory perception. But another important reality demonstrated in these interviews is that artists express easy and widespread disapproval of Chinese art criticism, which originally should be the embodiment of rational inquiry. Contrasted against the vagueness of their beliefs and their universal approval of business, this attitude bothered me as I wrote this article.

A painter who is the director of an important museum of fine arts had this to say about art critics:

“Basically there’s no need to listen to their views… [Criticism] is a translator. A lot of people need it to translate for them because they fail to understand, or cannot enter into your artistic world. Critics have absolutely no authority to guide artists.”

Another important senior artist said, “I don’t pay much attention. There are only one or two critics I respect. If they can see just one or two important qualities in my work, I give thanks to God. I have my doubts as to whether China has any critics at all… The books I see don’t have their own points of view. They don’t point out the overall shape of historical development.”

When discussing art criticism, the majority of the artists did not make specific criticisms of criticism. Instead, they directly expressed their unfamiliarity, neglect or dismissal of art criticism. Many people attempted to wash their art free of any connection with Chinese art criticism.

Art theory is a search for justification for the existence of art, and criticism is the principal interface through which theoretical study and creation come into direct contact. It is not just a tool for “translating” or “finding qualities” in works of art, and of course it can’t rely on any “authority” to guide artists.

We need to understand that people’s understanding of art is an important part of art. Through studying this understanding, art criticism allows individual bursts of artistic energy to be brought back into social and historical systems of knowledge. It is an important reference for artists as they learn and create.

I believe that what has led artists to have such contempt for criticism might be the mediocrity or ineffectiveness of critics in a China where ideology is crumbling. Both the political propaganda in the past and the commercial market later on have treated criticism as a tool, and relegated Chinese art criticism to a low ranking activity. For nearly 30 years, critical activity in the field of Chinese contemporary art has struggled hard for the right to speak for itself, with obviously poor results.

But putting aside art criticism, what I want to ask is to what extent do we in today’s society still really believe any of our own ideological theories?

This is a difficult time for Chinese art criticism. At this point of fracture and chaos in ideological concepts, we lack the basic consensus needed to hold a discussion. That is to say, we lack a generally trusted body of knowledge. Many critics haven’t yet learned to read through a book written in a foreign language, but they have already forgotten how to write a sentence in Chinese. Their scholarship is just repackaged pieces of fashionable foreign culture. While the government is entrenched in its ideological taboos, Euro-American capital and the Euro-American art system are breaking upon us like a flood, like wild beasts. And reflections and judgments that have formed over time too often get misrepresented and obscured, or just vanish amid a confused hail of arguments and ideas.

Under such circumstances, if you want criticism to have any practical significance, all you can do is write articles in response to current events. In this way, practical success and failure have easily come to exert an influence as the most important evaluative criteria. Some critics have raised themselves up from theoretical work and become bureaucrats, curators, art dealers or auction consultants. They are intent on seizing territory and expanding their influence. In fact, this obscures the status of critical work even further and hurts its reputation.

During the 1990’s, the Western art system made its entrance, followed a few years later by the market. The emerging Chinese contemporary art market developed, and auction prices began to appear in the culture sections of newspapers, going on to make headlines. With an overwhelming advantage, and in the name of globalization, these factors conducted an epoch-making reappraisal of China’s art and artists.

I do not wish to defend the dilapidated state of Chinese art criticism here. But I do want to say that while artists abandoned the domestic critical system—not without a degree of utilitarianism—they at the same time gladly submitted to the market’s criteria and differentiation. Perhaps it is precisely because our world view is so battered, our beliefs so vague, because we have lost any conceptual standards and gotten rid of all authorities, that in the end all judgments have been happily taken over by the market and by capital. The interviews are a further corroboration that as ideology has crumbled in contemporary China the tradition of art criticism has been shattered.

Section Five

The final interview associated with this article is not one of these forty. It is my interview with Davide Quadrio. I thought I needed to know what his motivation was to do these interviews.

It was already late on that autumn evening when we met in a coffee shop not far from his home in Shanghai. There is little room, so we have to sit very close.

He starts by talking about how he first started the BizArt Art Center in Shanghai. In the late 1990’s, it was one of the first environments founded to promote the creation of contemporary Chinese art in a sustained way, to mount independent exhibitions and hold discussions about art.

However, on this evening almost ten years later, Quadrio feels that the original significance of BizArt has now disappeared. He says that now he has the money he needed in those days. He has the space. He also has a certain influence. But the art that appears inside has not grown and changed. He puts it very straightforwardly, saying “It’s no good.”

He explains why he interviewed 40 artists. Well, in Chinese, “four” sounds like “dead,” right? 40 artists plus 4 interviewers is 44: dead, dead. He says he did this because he wants to stop for a while, stop and seriously think things over.

As I write this now in December, his problem has been passed on to me and has become an embarrassment to me here in my house in Shanghai in the winter: why didn’t art stride forth into a rich and broad world, as had been hoped for in the beginning? Moreover, it seems as if this task insists on asking: in this era, when most artists express contempt, when people in the theory businesses are trying to change fields, throwing themselves into the service of capital and the market, why should I continue writing?

One very direct answer is that, just as when contemporary Chinese art began to take root, or when Quadrio started the BizArt Art Center, a lot of our work is born out of discontent.

But this does not mean that I want to use criticism as a private tool. If we assume that our work is to lay the ground for the history of art that must necessarily come to pass, or better yet, to become a guide for art history as many professionals hope, then it is still in service of some object. I myself am closer to the statement of one of the artists interviewed. If critics take this as a mere profession, then perhaps they are not looking with complete sincerity.

Therefore, as with creation, commentary might be able to have its own motivation and point of departure for art, and use this to witness the completion of art from creation to understanding. This sort of writing would be an intellectually and emotionally necessary vivid portrayal of art. Although art has always been enmeshed in the vain world of money and power, it is precisely because of this that the purity and tension of its spiritual orientation has shown itself to be so important. In the end, art is related to the force and direction of how individuals understand the world.

Put this way, I am more than justified to say to artists who lack consideration for transforming world views: if you depart from the pursuit of some good, if you have no way of knowing what excellence is, then your art will be little more than debris. To the young generation that loves to make easy declarations of diversity, that belittles value judgments, that has a jaded understanding of democracy and equality, I say: without excellence, who knows what art is!

In art, we bring forth our own fundamental views of the world and embark on a discussion of what a more complete world might be. This is what my writing will be about. The ideal of transforming world views is the ideal of the possibility of a more reasonable and better social existence. Excellence is our expression of brilliance through action. In this time of shattered concepts, the emphasis on excellence calls to account this retarded era that has lost and abandoned the ability to make value judgments.

What is art history? Art history is the course of people using art to express excellence. It does not necessarily tend toward elitism, just as throughout the history of art, people have constantly been aware that elitism is inadequate.

The modern argument that “everyone is an artist” is well intended. It is not an attempt at passing off paste as pearls. It is because we all have unequal abilities that we have a desire to pursue equality. The pursuit of equality comes precisely from the demand that humanity be more comprehensively excellent. As reflected in some of our traditional thought, it is between excellence and equality that the world shows a healthy aspect of dialectic and approaching balance.

Section Six

According to many of the interviewees, it is difficult for even the people closest to them to understand the art they insist on pursuing. The people around them “feel it is illusory,” that “it just isn’t sound.” Because what they do is so bizarre, those who pursue contemporary art find it even more difficult to explain. This situation only improves later, because they start making money.

Aside from these professional obstacles, during this period, or even earlier, there has been a widespread misunderstanding or lie that art and artists have a vision of the future, or that they are capable of prophesy. Of course this has been the view in the West since the Enlightenment. China’s past cultural tradition did not lay emphasis on literati artists having this ability, be it innate or acquired. When it comes to predicting the future, it would be very difficult to tell if art and artists are better at this than other groups or other fields. But this more or less baseless arrogance, this supposition, fabrication, even mythification of one’s own extraordinary ability, has often led artists to put art and themselves in an unequal relationship with the people around them.

In the end, do artists want to keep their distance from the people in their daily lives? An example from outside the interview is a young person who was admitted to an academy of art in a major city. His mother thought that from then on, every year when he came home for Spring Festival he would be able to make some money by helping people to write their spring couplets. But he wanted to escape. The art that he learned did not resemble writing spring couplets at all in its relationship to people and its place in society. Even if he were to write couplets, he wouldn’t think of that as art. Mother and son deeply misunderstood each other when it came to art.

This gap is probably exactly the relationship between the art of most of the artists in the interviews and the people close to them. What I see is that art has been stripped from people’s lives─ from life in the historical continuum─ and has become its own game, a game it plays with itself.

When asked in the interview what art’s greatest contribution to society is, the artist Zhu Julan said:

“In the past there was no concept of the artist, properly speaking. I am talking about in ancient times. He was first and foremost an intellectual. His knowledge and everything he did displayed great cultural accomplishment, and he influenced many people around him, perhaps by writing poetry, perhaps by painting, or perhaps through something else. Now, maybe the culture of an age is created by people like that. That is to say, after people have created for generations and generations, we are left with a very rich or great tradition… I feel it is different today. A lot of artists treat this as a profession, just something he does for his own livelihood. Maybe all he is considering is his own life.”

I agree with his view. But we are also confronted with another attitude that is seemingly unselfish. One artist highly regarded in contemporary art circles said, “In fact (making a work) is just expanding these standards, you could say changing these standards.”

In the words of this artist born in the 70s, those standards are the standards for what is “fun,” “interesting” or “amusing.” At the same time, he said, “I don’t really think there are standards, because if there were standards then there would be no need to implement them.” The expansion he wants to do is to allow the boring to maybe also be fun, allow the unamusing to maybe also be amusing. But is it really fun or amusing? There is no standard, and he doesn’t really care.

His words are representative of the logic of Western contemporary art as it has developed from Marcel Duchamp’s urinal down to the present. Originally, Duchamp was opposed to art imitating an “object.” But later a distorted expression of his philosophy of art became the “object” of imitation for art today. The problem I really want to express here is that those artists so typical of contemporary art today who take changing standards as their artistic goal do not care about standards at all. For this reason, their change is not a transformation. It has no driving force for good. This kind of art wants to free itself of from standards of judgment, leaving only change itself as the ultimate value judgment. The result is a constant attack on standards.

One of their influences, Joseph Beuys, was an advocate of creativity. He tried to extend the outer edges of artistic concepts into all fields without limit. But in a dialog in the early 1980s he explained that it is only the innovative part of any field that is art. This makes it clear that the standards of a field are important. Moreover, Beuys was famous for his insistence on a progressive world view. Therefore, when he advocated breaking standards, it certainly did not imply grabbing just anything at all to try it as a standard.

A standard that has been established for a period of time becomes a social convention. In the end some people’s art has become an untiring retaliation against the public nature of art. Since the beginning of the 20th century, when Western artists have wanted to break out of the frame, they have claimed that they want to seize art from the hands of the aristocracy and return it to the people. With the arrival of postmodern discourse, this changed into a mild inquiry into changing the public nature of space. But the contemporary art that has developed from this has headed straight into an isolated loop, selfishly using art to provide pleasure and achievements for a small circle.

I do not want to conduct an in-depth study of individual artists’ work here, but this has led me to see a response to Quadrio’s problem that is related to the lack of thinking about world view among artists: the role that contemporary artists have given themselves, their deviation from communality, and so on, all reflect a major deficiency.

Section Seven

Over the last several decades, Chinese contemporary art’s orientation toward forcing great changes on China’s visual perspective has learned from the West and fought against domestic inhibition. Although it has encountered heavy resistance throughout this course, introspection on the part of artists and critics has never ceased. However, is this introspection enough? Is it enough to raise us up from the current pervasive retardation and utilitarianism?

Throughout these years of writing, I have often asked what intellectual resources we need in order to grow artistically. This has implications for this era of construction, for how do we manage intellectual production and establish our intellectual background.

These interviews show us a portrait of artists of different ages, including some artists who are not part of the contemporary art movement, and some bureaucrats in arts administration who used to be artists themselves, and so on. Over the past few decades they have experienced longer or shorter periods of social change in China. They have varied backgrounds. Today there is no longer any traditional growth track for Chinese artists.

But I can’t help thinking that right now we are actually faced with the possibility of forming a new tradition for artists. If you understand this to mean nothing more than preparing curriculum vitae listing exhibitions joined, as the Europeans and Americans have taught us, then you are wrong. Those things look hypocritical and unreliable, just like warranty cards. Nor do I mean today’s duplicitous and increasingly commercialized art academy education and the system of arts institutions we have modeled entirely on on the Western plan. The artists’ tradition that I am talking about is: in the end, what are the social and cultural resources and art historical threads that have forged artists’ background and vision?

This is a big question, a long and difficult road. Once such a new artists’ tradition is formed, we will have a new genealogy of artistic understanding and study. Even more optimistically, this will also provide the foundation on which we will construct our art theory. Therefore, how are we to extract ourselves from the current frenzied art market, transform our world view beyond the new experience of all this money and all these things, consider art in a longer flow of history, and reshape the relationship between contemporary Chinese art and the outside world? Rooted in our own cultural history and the standpoint developed in the modern and contemporary West, how are we to respect knowledge and experience? How are we to examine, reflect on and renew our attitude toward the world?

If there ever was an art like that, it has left us, left itself, to go search for greater strength. I hope there comes a day when it will return to the world again with its profound grasp of human life and its tremendous sentiment, and enter once again into our unbroken social life.

Except where noted, all artists’ quotes are taken directly from the interview transcripts.