The Secret Li(f)e of Chinese Contemporary Art, by Roberta Lombardi

“Culture” and “art” can no longer be simply extended to non-Western peoples and things. They can at worst be imposed, at best translated. – James Clifford

It exists an education of the taste that has the gradual effect of masking, instilling arbitrary notions, the arbitraries of the notions instilled. – Pierre Bourdieu

Civilization is just a chaotic jumble of rags and scraps. –Robert Lowie

Thirty years after Deng Xiaoping’s first reforms for economical opening, the Chinese art world has surely reached goals that were unthinkable before, giving artists, curators and dealers many more chances to live and work. Here everything is being constructed and transformed; such speed is only possible in China.

The great rush, the excitement and the shortcuts that have been taken, have created a reality that is contradictory and hard to define. For this reason, this art world is still an unpredictable context, where periods dominated by a strong censorship that recalls the Maoist age switch to moments of great experimentation and artistic maturity.

As it had planned, China is now one of the world powers leading the globe: a newly feared and respected driving force of our future.

It is still difficult to know which role Chinese contemporary art will gain in the international art system, how many art-workers there will be and which influence they will have. We are talking of those – out of the one billion and a half Chinese people – who will decide to work in art as collectors, dealers, curators or artists.

There are few moments in which China has not been a leader nation. But today our reality is very different from the past. Due to globalisation, our world has turned much smaller and interdependent, so that what is happening in China concerns all of us more and more closely. Obviously the West is scared by this “forced” proximity, and the growth of countries like China and India is becoming a new challenge. The battlefield is not only the market, but also culture and the question of freedom and human rights. It is true that, for instance, the economic success of nations that have neither trade-unions nor a welfare state system can bring about a loss in workers’ and human rights in the rest of the world.

However, Western countries, while promoting certain values and rights, have not always followed these values closely. More than once they did not hesitate in taking advantage of convenient circumstances, while easily forgetting dramatic facts as those of Tiananmen Square in 1989. The strong process of globalisation has brought to light new issues that a Eurocentric perspective could have once ignored.

Already in the Fifties, people from Asia, Africa, the Pacific islands, Arabs and American and Australian natives have claimed their state of dependence from Western hegemony.

“Orientalism” [1], an essay by Edward Said, criticized the Western attitude in dealing with the “Orient” as a homogeneous and stereotyped reality. Orientalism is a “style of thought based upon an ontological and epistemological distinction made between “the Orient” and (most of the time) “the Occident”” [2] as well as a “corporate institution for dealing with the Orient” [3] for “dominating, restructuring, and having authority over the Orient” [4].

The key issue of this book “concerns the status of all forms of thought and representation for dealing with the alien” [5]. Even if criticized for his deeply polemic spirit and for some internal contradictions, Said has succeeded in calling into question a certain number of important anthropological concepts, first of all that of “culture.” In this sense, the author has questioned the idea of the “West” itself: today we still tend to speak about “the West” and “Western culture,” because it is more practical and simple; Said himself spoke of Western countries as a whole, aggressive and hegemonic reality.

At times though, Said permits us to see the functioning of a more complex dialectic by which a modern culture continuously constitutes itself through its ideological constructs of the exotic. Seen in this way “the West” itself becomes a play of projections, doublings, idealizations, and rejections of a complex, shifting otherness [6].

Being aware that neither the “West” nor the “Orient” actually exist, we realise that there are just different places, reached by a globalization which has caused different reactions and feedbacks. This brings not only more homogenization or “americanization”, but also the creation of an unbelievably versatile and complex system, where personal and collective identities are never given, but are the result of a continuous negotiation. Quoting anthropologist Arjun Appadurai: “If a global cultural system is emerging, it is filled with ironies and resistances, sometimes camouflaged as passivity and a bottomless appetite in the Asian world for things Western” [7].

Thanks to the very active exchange between the “West” and what has been defined as the “Third World,” the growing globalization process is transforming the way of thinking and acting of the “First World” itself. For instance, it has been pointed out – mostly following exhibitions such as “Primitivism in 20th Century Art–Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern” that took place at MoMA, New York, in the winter of 1984-1985, or “Magiciens de la Terre”, at Centre Pompidou, Paris, in 1989 – how much the notion of “art” itself is all but a universal idea. It is rather “a changing western cultural category. […] That this construction of a generous category of art pitched at a global scale occurred just as the planet’s tribal peoples came massively under European political, economic, and evangelical dominion cannot be irrelevant” [8].

So, what I would like to do here is look at the “contemporary Chinese art” phenomenon as well as at the Chinese and international art system in this perspective. Quoting Hou Hanru, we can say that a “different kind of modernity exists and the coexistence of modernities has important consequences today because of the active participation of different cultures in the making of a global culture. So, when we talk about contemporary art, the dynamism generated by these differences can continuously bring about new definitions of what we call contemporary art. In a way it is important to look at Chinese art from this angle” [9].

Also because of the lack of a deep knowledge of Chinese current and past events, the attitudes that have commonly influenced the way of looking at Chinese contemporary art from the outside have been concern, suspicion and cultural snobbery, or a superficial “business making” interest.

Suddenly, after the Chinese economic boom, Chinese artists’ works appeared on the international stage, smartly set in glamorous art shows of “Chinese contemporary art,” more and more frequently hosted by art galleries. The “Chinese contemporary art” has become a brand, a subgroup of international contemporary art.

The trend of “Chinese contemporary art” has maybe responded to a need of the by-now bored international artistic milieu; in a decadent era, characterised by “weak thinking” and “postmodernism”, it has injected fresh ideals and energy, in addition to creating new goods and buyers, essential to the life of the system. Perhaps it has also provided a good dose of self-esteem for the “West.”

How could Western culture not gain a confirmation of its “Truth” and “Justice” – now that it looked as if it were undergoing a period of crisis – by a comparison between Western “democratic” nations and the Chinese regime against which – according to its politicised way of seeing – Chinese artists were fighting?

Maybe another reason that made the Chinese Avant-garde [10] – that stands for “Chinese contemporary art” – so fascinating to Western eyes is the fact that these artists had strength and an “enemy” – the Communist regime – while in our “mature” democratic society, the “enemy” – that is, all that limits our freedom and rights – is dissimulated in a much more ambiguous and subtle way.

In a sense, there is also a sort of flashback of an apparently lost reality – in this case the Golden Age of Western “avant-gardes.” Fredric Jameson (1989) [11] defined this feeling as “Nostalgia for the Present,” typical of the “post-modern” condition [12].

But we saw that 21st century China does not bring us only back to our past, but also forward in our future. This is also due to a local cultural policy aimed to underline Chinese modernity and dynamism, which should be at the same level of the “West” or even overtake it. For instance, a great new media art exhibition, created by Zhang Ga, a Chinese curator living in the U.S., has been hosted at Beijing National Art Museum in occasion of the 2008 Olympic Games [13]. The relation between art and new media technology is seen under the lens of the divertissement, hardly connectable to a political or subversive discourse. The government cultural policy favors artistic activities dealing mostly with entertainment: big glamorous events that the wide audience can easily understand.

Finally, I suspect that the fact that Chinese and non-Western artists desire to work according to international standards and to fit in the international artistic context – international here meaning Western– creates a sort of “multiculturalism” that stands for another attempt of cultural and economical predominance from the West.

Globalisation entails the risk – not only outside the West – of “weak” cultures vanishing in front of the homologation lead by a dominant culture, or rather, by a dominant economy. The preservation of a “culture” is not an easy process: first of all, because we are still discussing the concept of “culture” [14], a word that is often exploited for fairly less cultural purposes; secondly, because a preservative attitude can produce conservatism or “ethnic hybrids” that appear more like goods than like cultural values. The identity and cultural question is something that Chinese artists are very sensitive to.

“Obviously it is not a problem that can be resolved by simple-minded, romantic promotions of the historically repressed “indigenous” cultures. On the contrary, apart from its positive possibility of “opening”, it is difficult to avoid the risk of falling into “political correctness,” whose main concern is to build new walls. In a worse case scenario, it is also prey of the central power’s “postmodern” strategy of “la mode rétro”, which, rejecting “les Grands Récits”, turns everything into ephemeral fashions and hence cuts off the connection with cultural engagements in real life” [15].

Moreover, contemporary art has become a “cultural box” that can be exported to build a sort of transnational community [16]. At the 2007 Venice Biennale, the opening of the African Pavilion raised an outcry; it is more and more fashionable to host exhibitions in peripheral areas or to invite “Third World” artists, coming from economically weak or at war nations. These artists are expected to bring a “traditional,” non-Western view of contemporary art.

Nevertheless this desired pluralism, that such circumstances should ensure, is rather superficial seeing that the interpretative (and selective) greed is, again, a Western one.

As Hou Hanru noticed: ‘“New Internationalism” differs from previous internationalism, represented by, for example, the Bauhaus and modernist architectural discourse, which tended to implant a West – centric utopian model on the world. A “New Internationalism” reflects the pluralisation of international political, economic and cultural relationships as well as the contradictions and conflicts that have emerged in the process […] One can easily discover that most of the investigations of “multiculturalism”, the self, the other, and related issues, have unfolded around an axis of a radical change in the relationship between the colonial master and the slave in the postcolonial period. What is interesting, even ironic, is the fact that, while being certainly one of the most important issue of “multicultural” studies, this axis has indeed monopolised the whole exploration of “multiculturalism”, as if its significance is decided by the extent of its relation to this axis. Here, one can discover an intention to redeem the colonial sins of the West, by destroying its “colonialist-Eurocentric” domination. The significance of multiculturalism has been too often dependent upon its connection to a self-correcting West. In other words, an “anti-West-centrism” is still aligned to another less visible but inescapable “West-centrism”’ [17].

On the other hand, we should wonder if it makes sense to speak about the “Chineseness” or “Indianity” or “Africanity” of contemporary art, in a historical period like ours, where there is a continuous flux of people, cultures, goods and “imaginaries”, created by mass media, while the “nation-state”, which was once based on a strong cultural identity, becomes more and more undefined by public transnational spheres [18]. Perhaps these attributes of “nationality” find more success on a commercial level than on a cultural one, and frequently hide mere economical agreements among the involved nations.

Besides, as Hou Hanru underlines, staying linked to the nationalistic logic means depending again on a power-logic.

“We continue to cherish the hope that by scrutinising history and memory we will rediscover the “national spirit” and so find a way of “going home”. We pay a price here however, because in doing so we subordinate our imagination and creativity to the dictatorship of a “monolithic cultural image” as defined by the authorities. […] It is actually the legacy of Western culture and their faith in “national identity” that makes Westerners expect Chinese to behave like Chinese people all the time so that they can be “understood” and hence controlled” [19].

It is keeping in mind all of these issues, that we might start to reconsider more clearly the art system (both Chinese and international), its dynamics and its future developments.

To look at Chinese artists’ production doesn’t mean we need to refer to the common dichotomy “we-they”: “the attention to Chinese art of the Western art scene still remains, in most cases, a consumerist relationship, instead of being a dialogue. I would hope to see more dialogue, but a real dialogue takes places only on an individual level. So, for the Western world, rather than considering Chinese art as an entity, it would be more beneficial to see the art as an individual statement instead of as a representation of a situation” [20].

Countries that lead the artistic world and its market maybe ask this from Chinese artists: an edulcorated “exotic” taste. An “Other”, which has been cleaned up and “glamorized.”

The “exotic” identified in China by the West in the past will be difficult to find today. It is also true that “exotic” is something “diverse” that doesn’t concern us, marking a limit or giving us a brief holiday from ourselves.

According to Victor Segalen, the passionate defender of exoticism, an exotic regard should never go across the wall which separates the Self and the Other; otherwise, the beauty will be lost [21].

It is much harder to accept the “diverse” that is near us. With this term I refer not only to cultural differences but also to the individual ones, all the more today where there are many factors influencing and transforming us, marking a fracture even among different generations.

Anthropologist Marco Aime ‘s words on the relationship between the West and the Dogon people from Mali, may not feel out-of-place here:

“Nothing serious, for God’s sake, just a curious phenomenon of our days where the encounter among two cultures is confined by the first, ours, in its spare time, while the second must ensure a form of amazement, but an amazement partially defined, not too far away from the pictures printed on travel catalogues” [22]. (And in our case, on art and other reviews).

Nevertheless, I don’t think that something different is asked from “our culture” as well as from “Western” artists; rather it looks like artists are expected to provide a luxury and elitist way of amusement, with a pinch of political and moral provocation and scandal, so as to provoke a shiver in front of the forbidden, but in a very superficial way, just to clear our conscience.

Art world is always hunting for novelties. Today, it looks like China is the right setting to fulfil these expectations.

But, as noted by the art critic Stephen Wright dealing with Shanghai, “On the surface, the Shanghai art scene appears vibrant: the economy is hot, and demand continues to outstrip supply. But beneath the seamless surface of bonheur and excitement, is there not a latent discontent — that is, an often only obliquely articulated frustration and disorientation with current norms and values?” [23].

Finally, as well as the “Shanghai case”, we might read the “China case” in a different light, nothing more than the representation of “what is occurring in the rest of the world as well: the fracture between the artist, his or her art, and the art world system” [24].

[1] Edward W. Said, Orientalism, Vintage books, New York, 1979

[2] Ibi, p.2

[3] Ibi, p.3

[4] Ibidem

[5] James Clifford, The predicament of culture, op. cit., p.261

[6] Ibi, p.272

[7] Arjun Appadurai, Modernity at large : cultural dimensions of globalization, University of Minnesota press, Minneapolis, London, 1996, p.29

[8] James Clifford, The predicament of culture, op. cit., p.196-7

[9] Exceptions to the rules, interview with Hou Hanru by Lotte Philipsen, in A.A.V.V., Made in China, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebaek, 2007, p.33

[10] Cf. Gao Minglu, The wall : reshaping contemporary Chinese art, Buffalo, NY, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Pékin, Millenium Art Museum, 2005, p.45 «We must accept the fundamental premise that in the twenty years since the 1980s, Chinese artists and critics have used the term “avant-garde” to define China’s new, contemporary art.The use of this term – including Chinese artists’ misunderstanding of it as well as Western interpretation of China’s “avant-garde art”- has become a fundamental, structuring part of the history of Chinese contemporary art»

[11] Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism, or The cultural logic of late capitalism, Duke University press, Durham, 1991

[12] Cf. also A. Appadurai, Modernity, op. cit., p. 30-1 «The past is now not a land to return to in a simple politics of memory. It has become a synchronic warehouse of cultural scenarios, a kind of temporal central casting, to which recourse can be taken as appropriate, depending on the movie to be made, the scene to be enacted, the hostages to be rescued. […] If your present is their future (as in much modernization theory and in many self-satisfied tourist fantasies), and their future is your past […], then your own past can be made to appear as simply a normalized modality of your present. »

[13] “SYNTHETIC TIMES – Media Art China 2008”, curated by Zhang Ga, Jun 10 – July 3, 2008, National Art Museum of China (Namoc), Beijing

[14] Cf., for instance, James Clifford, The predicament of culture , op. cit, p.231: «It is increasingly clear, however, that the concrete activity of representing a culture, subculture, or indeed any coherent domain of collective activity is always strategic and selective. The world’s societies are too systematically interconnected to permit an easy isolation of separate or independently functioning systems. »

[15] Hou Hanru, Facing the wall of the future, written in occasion of the Second Asia-Pacific Triennal of Contemporary Art, Queensland Art Gallery, 1996, in Hou Hanru, On the Midground, Timezone 8, Beijing, 2003, p.97

[16] Referrig to “trasnational”: cf. Ulf Hannerz, Transnational connections : culture, people, places, Routledge, London, 1996, p.9: «the term “transnational” looks humbler and often more suitable for labelling phenomenon variable for scale and distribution, also when they share the characteristic of not being limited by a single state. [ …] it is important to underline that many connections are not “international” in the strict sense of involving nations – that is, states – as institutional actors ».

[17] Hou Hanru, Entropy, Chinese artists, western art institutions: a New Internationalism, in Hou Hanru, On the Midground, op. cit., p.54

[18] Cf. A. Appadurai, Modernity, op. cit., p.36-42

[19] Hou Hanru, A certain necessary perversion, taken by the catalogue Heart of Darkness, Kroller Muller Museum, Otterlo, 18.12.1994-27.3.1995., in Hou Hanru, On the Midground, op. cit., p.106-112

[20] Exceptions to the rules, op. cit., p.32

[21] Hou Hanru, Facing the wall of the future, written in occasion of the Second Asia-Pacific Triennal of Contemporary Art, Queensland Art Gallery, 1996, in Hou Hanru, On the Midground, op. cit., p.95

[22] Marco Aime, Diario Dogon, op. cit., p.16

[23] Stephen Wright is introducing the installation project and documentary created by Davide Quadrio together with Lothar Spree, Zhu Xiaowen e Xu Jie. The project consists in the interviews of 40 artists and 4 curators dealing with the relation among artists, their art and the development of art system in Shanghai in the latest twenty years. Cit. in Davide Quadrio, Once again: China!, in A.A.V.V., Cina, Cina, Cina!!!, Silvana Editoriale, Cinisello Balsamo, 2007, p. 58

[24] Davide Quadrio, Once again: China!, in A.A.V.V., Cina, Cina, Cina!!!, op. cit., p.58

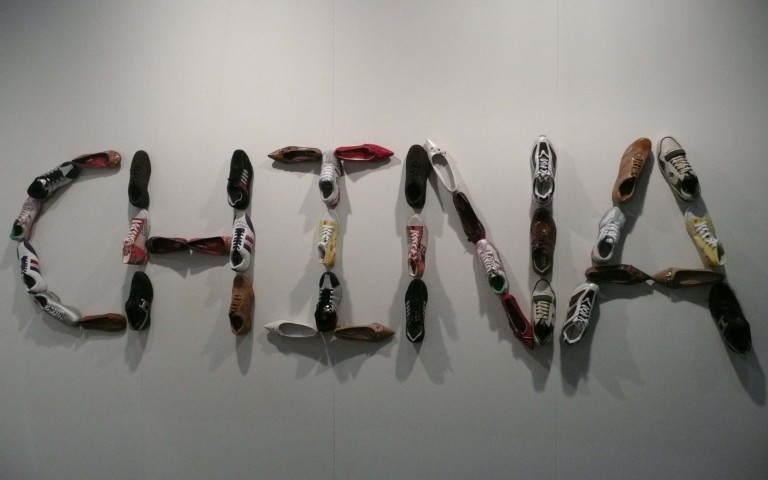

Note: the image on the banner is China, 2007, cm 90 x 360

Collezione Mauro Corinaldi, Milano in accomodato all’Università Bocconi di Milano, Courtesy Galleria Umberto Di Marino, Napoli

Roberta Lombardi works as a curator and writes in the culture section for the daily newspaper Il Riformista, Roma and the weekly magazine Zero_, Milan. She is currently collaborating with Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Torino, for the production of ten videos of young artists. She has worked with Cardi Black Box gallery, Milan, Flash Art magazine and Musée du Louvre, Paris.