Situating Socially Engaged Art in China by Zheng Zhuangzhou

This text is based on the paper by Zheng Zhuangzhou given in the occasion of “Negotiating Difference Contemporary Chinese Art in the Global Context”, in Berlin, October 2009.

Within the past few years, a number of socially engaged art projects have emerged in China. Let me give you three examples.

In 2005, documentary filmmaker Wu Wenguang initiated the China Village Documentary Project. When the EU-China Training Program on Village Governance asked him to produce a documentary on village self-governance in rural China, he made a counter proposal: rather than making the film himself, he would help farmers to document village politics themselves. He placed an advertisement on Southern Weekend, a popular newspaper, calling for proposals. He selected ten submissions, invited the farmers to his studio in Beijing, trained them for a week, and gave each person a low-end DV. These ten farmers came from nine different provinces, their ages ranging from 24 to 59. They went back to their villages and captured elections, discussions, disputes, and everyday life. They then went back to Beijing and Wu Wenguang’s team helped them to edit the footages into ten short videos, each lasting for ten minutes.

In one video, Nong Ke, from Guangxi province, filmed how his fellow villagers decided the distribution of the 10,000 RMB they received from the government to support pig farming. The entire village gathered in an open space. The village head wrote names on a brick wall, placed bowls under the names, and gave each villager a number of beans to cast their votes.

The collection of these ten short videos was screened at numerous film festivals in and outside China, exhibited in the 2007 exhibition Grassroots Humanism held in Song Zhuang, and was broadcast on CCTV.

The second one was a multimedia research project led by Ou Ning in 2006. It was about the urban renewal of Da Zha Lan, a historic area just southwest of Tian’anmen Square. Ou Ning gave video cameras to several residents who faced relocation. One resident, Zhang Jinli, fought resolutely for a fair compensation for his property. He captured his struggles on tape, providing much of the raw footage for the video titled Meishi Jie. In one memorable sequence, when the police came to his home to announce the government’s final resolution, Zhang Jinli filmed the police while one policeman was also holding a video camera filming him. I feel that Zhang Jinli’s camera was charged not only with battery, but with courage and defiance. I have seen this work in two occasions in Beijing, at an exhibition on urbanism held in the headquarters of a media company, and at a screening in the Iberia Center in 798.

The third project is Karibu Islands by Zheng Bo. It started in 2004 as a series of experimental videos about an imaginary place where time travels backwards. This time reversal hypothesis leads to many possibilities. For example, on Karibu Islands, human lives would be experienced backwards. People would be born old. Many would wake up in a hospital; some in a battlefield; JFK would have come to life when a bullet came out of his brain. People would gradually become younger and healthier. They would go to work, then attend school, then become babies. Eventually they would leave this world by climbing into their mothers’ wombs. On Karibu Islands, concepts such as economic development and social progress would also take on different meanings.

In 2008, Zheng Bo situated this project within the queer community in Beijing. He organized a series of games and discussions at Beijing Queer Cultural Center, established in April 2008 by two leading queer activist groups, Aizhixing and Tongyu. 11 gay men, 9 lesbians, and 13 straight people participated in the discussions. They first watched the videos about Karibu Islands, and then, each person filled out a “Birth Certificate,” by imagining her condition at birth: age, health, sexual orientation, openness, family composition, assets, wisdom, values, life plans, etc. The groups then got together to compare and discuss their imagined lives. These discussions allowed queer and straight participants to project their ideals onto an imaginary site, and approached issues of sexuality from an alternative perspective. This work was shown in the 3rd Guangzhou Triennial in 2008 and the first queer art exhibition held in Beijing this summer.

These three examples provide a glimpse of an emerging socially engaged practice in China. Artists collaborate with specific communities to address social issues in creative ways. Western critics like Grant Kester and Claire Bishop have located several aspects unique to this practice. Socially engaged art adopts “a performative, process-based approach” rather than the traditional one of object making; artists are “context providers” rather than “content providers”; projects aim to intervene and transform current situations rather than merely represent them.

I see another clear distinction between socially engaged art and traditional art practices: socially engaged art utterly depends on the public sphere for survival. Socially engaged art comes into being only when a public is convened to discuss a public issue in a public space. This is why artist Suzanne Lacy and others coined the term “new genre public art” in 1994 to foreground the public quality of this art and to distinguish it from the traditional concept of public art, narrowly understood as sculptures erected in public spaces.

There has been much debate among scholars on whether the public sphere exists in China. According to Habermas, for the public sphere to come into being, “public discussions about the exercise of political power” have to be “both critical in intent and institutionally guaranteed.” There is no institutional guarantee of freedom of speech and association in China today. Yet market reform and social changes of the last three decades have unleashed a set of forces that demand the growth of the public sphere and civil society, regardless how much the state is trying to contain it. Although the public sphere, in the Habermasian sense, is nonexistent, multiple publics are arising. For example, the queer public in Beijing is very active, supported by activist groups like Aizhixing and Tongyu, publications like Spot and Les+, websites like boyair.com, and over a hundred QQ groups that facilitate online discussions and offline activities.

The three projects I described above are embedded in the emerging publics. They were realized in public spaces, received support from public organizations, and circulated in public exhibitions. In turn, they made public issues visible, enabled public dialogues, and contributed to the development of a public consciousness.

I would like to argue that the symbiotic relationship between Chinese contemporary art and public sphere(s) is actually not a new phenomenon. If we take a close look at the history of Chinese contemporary art, we will realize that throughout the last three decades, the notion of publicity, publics, and public spheres have provided continual momentum for contemporary art – ideologically, organizational, and aesthetically. And contemporary art in turn has played an important role in efforts to develop the notion of publicness. This is the topic of my PhD research. In the remainder of this presentation, I will briefly discuss one example in the early period of Chinese contemporary art.

The history is familiar to everyone here. On September 27, 1979, a poster was placed in front of the National Art Museum, informing visitors that the Stars Outdoor Art Exhibition was being held in the small park east of the museum. In that early morning young artists like Ma Desheng, Huang Rui and Li Shuang had hung their artworks on the fence between the museum and the park. The fence clearly marks the separation of the state sphere and the public sphere. The artists couldn’t gain access the National Art Museum, which is a state institution, but they were entitled to the park, which is a public space. Two days later, the exhibition was removed by the police. The artists responded with a demonstration on October 1, National Day. After some negotiation mediated by the Artists’ Association, the government agreed to return the artworks and allowed the exhibition to continue in November in Huafang Pavilion in Beihai. A year later, in August 1980, the second Stars exhibition was held inside the National Art Museum, attracting over 100,000 visitors.

The Stars exhibitions in 1979 and 1980 have acquired the status of a legend, symbolizing the birth of Chinese contemporary art. However, this exhibition trail – from the park next to the museum, to Huafang Pavilion, and finally to the National Art Museum – was only part of a bigger picture. In October 1978, almost one year before the first Stars exhibition, another trail – integrating literature, art and politics – began in Wangfujing, just south of the National Art Museum. Huang Xiang and a few fellow literary youths from Guizhou province posted a set of poems collectively called The Fire God Symphonic Poems on the wall next to the compound of People’s Daily. According to Huang Xiang, those poems were meant “to oppose the idol worship of Mao Zedong and his personal cult, to criticize romanticism, feudalism, fascism, and modern emperorship, to completely negate the Cultural Revolution, and to appeal publicly for freedom, democracy, and human rights.”

The poems were written in the form of dazibao, a medium popularized in the Cultural Revolution. It gave those who had no access to state media – newspaper, radio and local broadcasting system – a cheap and accessible way to express their opinions.

By December 1978, cultural and political activists had gravitated to Xidan, west of Tiananmen Square. Many posters appeared on a wall next to a busy bus stop. The wall soon acquired its historic name, the Democracy Wall.

The Democracy Wall functioned as a transient public sphere. The site was accessible to the public. The central debate was whether China should move away from “the dictatorship of the proletariat” and “the eternal class struggle” to democracy. The most well-known piece of writing was posted by Wei Jingsheng on December 5, titled The Fifth Modernization. Wei called on the government to add another modernization – the modernization of democracy – to the official slogan of “Four Modernizations,” that of agriculture, industry, science, and defense. Wei criticized Mao Zedong, calling him a dictator. He drew parallel between Mao’s China, Stalin’s USSR, and Hitler’s Germany, describing them as fascist, antidemocratic regimes. Wei performed a relatively calm analysis of the past and the present in order to argue for a democratic future.

However, Wei’s conceptualization of democracy was highly schematic. He did not articulate the institutional and legal reforms required to transform China’s political system; neither did he understand the significance of the public sphere in the formation of public opinions that would cast criticism and control over the state. In fact, the word “public” never appeared in Wei’s treatise, even though he was engaged in a movement that took the very form of the public sphere.

The Democracy Wall Movement consisted of more than posters on the wall. The formation of independent groups and journals constituted efforts to institutionalize the movement. On November 24, 1978, Huang Xiang and his friends declared the founding of the Enlightenment Society. Other groups quickly followed; many started to publish journals, such as Beijing Spring, Jin Tian, and Tan Suo.

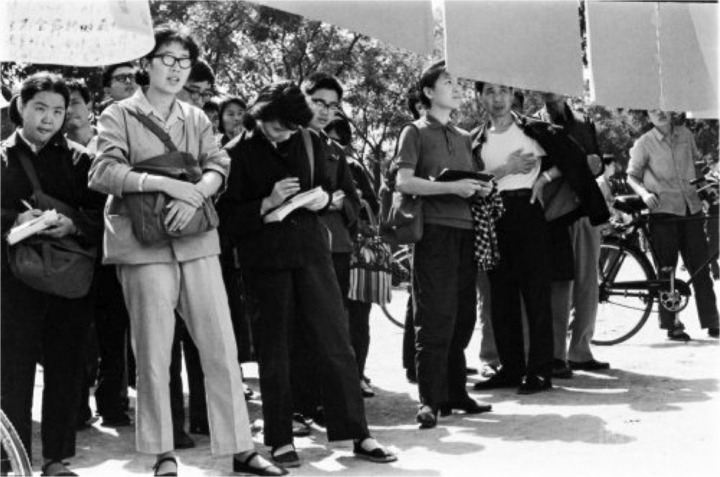

Most members of this public were young and educated. Their political radicalism was accompanied by their cultural liberalism. Huang Xiang and others continued to post poems on the Wall. This image was taken by Wang Rui, a young photographer from Jilin province, on September 3, 1979, a few weeks before the first Stars exhibition. It was titled Art Exhibition by Five Youths from Guizhou. In Wang Rui’s words, “This outdoor art exhibition took the form of ‘drying clothes on a string.’ [The artists] hung their works on the busy sidewalk. Exhibited pieces included oil paintings on paper and an artist statement. Those who stopped to look were mostly young people. Some were also taking notes seriously.” In other words, not only did artworks and political posters appear in the same site, the way the artworks were presented by the artists and received by the onlookers (“taking notes”) was remarkably similar to that of the political posters.

The Democracy Wall Movement came to a sudden end in December 1979, when the government decided to arrest almost all activists, with the exception of the Jin Tian members. Perhaps after one year’s existence, the wall had served its usefulness to the reformist faction in the Party, and the increasingly liberal discourse posed too much threat to the incumbent system.

I have outlined two trails: the Stars exhibitions, and the Democracy Wall movement. The two trails were intimately linked. The Stars exhibition emerged out of a political and cultural movement that constructed a transient public sphere. Art and literature shared with the political discourse an ideology centered on freedom and democracy. The format of outdoor, public exhibition of artworks closely resembled public display of political posters. Many members of the Stars group were also working on the literary journal Jin Tian. Although artists in the end turned to the state for authorization, they derived much of their energy from the public sphere.

Let me come back to the 2000s. I hope looking back to the recent past can help us to understand the present better. So what is different today? Here I will only outline some broad transformations. The recent emergence of socially engaged art is propelled by several larger changes in China. The state sphere is shrinking, however slowly. With the rise of the private sphere, the demand for the public sphere is also emerging. We witness today a desire for civil society, increasing visibility of activism, growth of NGOs, and a revived local interest in engaged art. The new socially engaged art projects differ from earlier efforts in several important aspects. The abstracted concept of “the people” has been replaced by much more specific publics: migrant workers, queer members, urban residents facing collective relocation, etc. Rather than interacting with the public via completed artworks, artists now work with the participants to create public discourses. Projects are often enabled by support from organizations outside the art field. Artists now frame their projects as social interventions, and avoid making explicit political claims. In short, socially engaged art has become more embedded in the multiple rising public spheres.

I hope my larger research project will contribute to a better understanding of the relationship between contemporary art and public spheres. The prevailing trend since the early 1990s is to turn to the market and the individual. I hope a review of history will demonstrate the importance of the public sphere and nudge the current discourse and practice of contemporary art towards a more public future.